PDF

PDF

1 College of Business Administration, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudia Arabia

Received: 05 June, 2025

Revised: 22 August, 2025

Accepted: 09 September, 2025

Published: 22 September, 2025

Abstract:

Objective: The study was conducted to evaluate the impact of climate change commitment (CCC) on the debt financing policies. It also evaluated the moderating role of institutional investors.

Methodology: The research adopted a quantitative approach using 150 firms of the S&P 500 based on market cap for 2010-2024 to capture the long-term impact. The data was analysed using Feasible GLS regression due to heteroscedasticity issues.

Findings: The findings highlighted that CCC significantly and positively impacted financing policies measured using debt to equity (β = 59.681, p = 0.000) and debt ratio (β = 14.287, p = 0.000). However, it did not have a significant impact on the interest coverage ratio (β = -0.983, p = 0.139). Furthermore, institutional investors negatively and significantly moderated the relationship of CCC with debt-to-equity ratio (B = -262.39, p = 0.000), debt ratio (B = -62.754, p = 0.000). However, it did not significantly moderate the relationship of CCC with interest coverage ratio (B = 1.09, p = 0.707).

Implications: As per agency theory, institutional investors can reinforce the credibility of climate-related commitments firms make when they commit to such objectives. These investors can further enhance these commitments through pressure for transparency, accountability, and long-term value creation. Regulatory authorities should promote or require climate-related disclosures, as CCC can impact financial decision-making, especially if backed by robust institutional controls.

Keywords: Climate change commitment, debt financing policy, institutional investors, S&P 500, debt ratio, financial decision-making.

1. INTRODUCTION

The global climate change challenge threatens the ecosystems and economies of the world; hence, there has been growing attention towards the sustainability policies of organisations. Many companies are experiencing increasing pressure from multiple stakeholders, such as institutional shareholders, government bodies, and consumers, to adopt proactive policies to deal with environmental issues (Bose et al., 2024; Flammer et al., 2021; Ooi et al., 2024). Climate change policies, disclosures, environmental technological advancements, and corporate social responsibility have become key components of firms’ sustainability strategies (Le, 2022). These pressures have greatly influenced corporate developments, especially in finance. Among these approaches, the role of Climate Change Commitment (CCC) in forming debt financing policies has been of keen interest among researchers. Businesses realise that it is not only an ethical responsibility but also a pertinent issue that represents the company’s solvency and possible risks to add environmental sustainability to their business practices (Lemma et al., 2021). In the case of S&P 500 companies, these pressures on sustainability are further accentuated, as big publicly traded businesses continue to come under more pressure and scrutiny from institutional investors and regulators (Yahaya, 2025). CCC is increasingly forming its financing plans, such as debt raising, in which stakeholders require transparency, risk reduction, and long-term value in line with environmental objectives (Hsueh, 2022).

Subsequently, institutional investors like pension funds, mutual funds, and hedge funds are assuming a progressively pivotal role in the governance of business conduct (Gu et al., 2023; Klettner, 2021; Yang et al., 2024). These investors apply criteria like ESG while considering companies, with the case that climate change is a threat and an opportunity that affects financial performance in the future. Institutional investors, as significant stakeholders in most organisations, can pressure companies to adopt sustainable goals by manoeuvring the companies’ business models and policies, such as debt management (Jabbour et al., 2020).

An important area of corporate financial management is debt financing, which concerns decisions as to how much debt to incur and on what terms. Socially aware and climate-concerned firms that want to improve CSR results may uphold more conservative debt levels because these organisations usually face risks related to climate responsibilities and large-scale sustainability projects (Ahmed et al., 2022; Cato, 2022). However, the study of (Shi et al., 2022) found that CCCs are likely to be partially mediated by debt financing policies owing to institutional investor pressure since these investors have leverage in the firm’s capital structure choice mechanisms. This is applicable as the present study investigates how debt financing by S&P 500 companies is influenced by climate change pledges, with institutional investors having the potential to moderate this relationship through their role in shaping capital structure choices.

In the context of the S&P 500, companies operate in a business environment where climate-related risks highly affect investors’ decisions, regulatory requirements and market expectations. These firms face increasing pressure from institutional investors, activist shareholders, and policymakers committing to ambitious climate change targets and demonstrating credible progress towards them (Hsueh, 2022). Simultaneously, they must make capital structure decisions in an environment of increased scrutiny, where excessive leverage can raise concerns about the company’s ability to finance large-scale sustainability projects and meet future climate-related obligations (Yang et al., 2024). It increases tension between maintaining financial flexibility and responding to stakeholder demands for meaningful climate action, particularly as lenders and credit rating agencies start factoring climate performance into debt risk assessments (Gu et al., 2023).

Furthermore, (UCLA, 2025) indicated that despite advances in climate disclosures, S&P 500 firms continue to grapple with challenges in proving a real commitment to climate change. There are gaps like incomplete cost estimates for transition plans, limited board-level monitoring, and low levels of environmental skills among directors. Scope 3 emissions, adaptation plans, and physical risk disclosures are underreported. Differences in data consistency, methodology, and limited reporting scopes impede comparability and accountability and strip stakeholder confidence. Without thorough financial planning, strong governance frameworks, and transparent, standardised reporting, companies risk failing regulatory expectations and investors’ demands. Improving these areas is critical to convert commitments into believable, actionable strategies that yield quantifiable decarbonisation and climate resilience. The study examined the impact of CCC on debt financing policies and the moderating role of institutional investors. The study considered a sample of 150 firms from the S&P 500 index over 15 years.

An increasing number of research studies have recently been related to CCC, such as (Albitar et al., 2023). The study of (Xhindole & Tarquinio, 2024; and Zhao et al., 2024) has taken this research further by providing evidence of CCC on debt financing of the firms. However, these studies have not considered other variables that might moderate this relationship. In line with the agency theory, institutional investors, as monitoring agents, can reduce agency conflicts between managers and shareholders. Their oversight can ensure that the CCC of managers is credible and aligned with long-term firm value, increasing lender confidence and impacting its debt financing (Ali et al., 2023). Therefore, institutional investors are an important moderating variable in this relationship. Despite this theoretical justification, empirical studies on this stance are limited.

Addressing the aforementioned gaps, the current study evaluates S&P 500 companies from 2010 to 2024, a context where investor scrutiny and climate accountability are high. The findings indicated that CCCS are significantly linked with conservative debt financing policies. However, the findings did not reveal the moderating role of institutional investors in the relationship between CCCS and debt financing policies.

The study contributes to the literature in three ways. It provides a theoretical contribution by challenging and extending the agency theory by emphasising the moderating role of institutional investors in the CCC-debt financing nexus. It adds to the empirical evidence on the moderating role of institutional investors. It offers insights for policymakers and investors on integrating climate considerations into corporate capital structure decisions and extends the application of agency theory to the context of climate-related financial decision-making in large publicly traded firms.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Climate Change Commitment (CCC)

CCC is an official promise of an organisation to reduce and respond to climate change by policies, plans, and measures to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, increase energy efficiency, adopt renewable energy opportunities, and incorporate environmental concern into the business operations (Kotz et al., 2024; Mohy-ud-Din et al., 2025; Zhou & Zhong, 2025). This dedication can be frequently fulfilled in terms of climate disclosure, investment in carbon neutrality, green technologies, and international frameworks such as the Paris Agreement or the Science-Based Targets (Bjorn et al., 2021; Mukhopadhyay & Sarkar, 2021).

CCC research has moved beyond concept definition to the modelling of its organisational impacts. To establish a relationship between corporate CCC and internal organisational competencies and external stakeholder relations, (Boiral et al., 2012) developed a conceptual framework and showed that the former may generate competitive advantage. Similarly, (Littlewood et al., 2018) studied the high-emitting sectors in European countries and identified strategic, regulatory, and reputational drivers as the main causes of CCC, focusing on the companies that were more likely to react to a combination of market pressure, stakeholder activism, and competitive positioning. The article by (Jangid & Sharma, 2025) demonstrates empirical evidence in the Asia-Pacific area that good climate commitments are associated with better carbon performance due to regulatory alignment, technological innovation, and expectations of investors.

Nowadays, CCC gains more and more relevance when climate change begins to inflict serious harm to the global ecosystems, economies, and social structures. Not only are companies major carbon emitters, but they also face certain physical risks (such as extreme weather) and transitional risks (including regulatory changes) (Chen et al., 2022; Tavakolifar et al., 2021). CCC thus indicates a firm’s forward-looking approach in managing environmental footprint and long-term business risks. It is highly relevant for organisations today due to changing expectations of stakeholders, such as investors, customers, regulators, and employees, who increasingly expect accountability and sustainable practice (Birindelli et al., 2022). For investors, CCC is a critical marker of a company’s risk exposure, governance standards, and resilience. For companies, robust climate commitments can build reputation, appeal to ESG-oriented capital, and drive compliance with upcoming regulations, making CCC an integral part of contemporary corporate strategy and financial resilience (Ali et al., 2023).

From a corporate significance perspective, CCC performs various functions. As a signal for investors, it signifies a firm’s exposure to environmental risks, governance quality, and long-term value creation ability. For companies, firm climate commitments can consolidate stakeholder trust, secure capital from sustainability-oriented funds, and raise reputational standing in increasingly climate-responsible markets (Birindelli et al., 2022; Jangid & Sharma, 2025). Additionally, proactive CCC enhances lender attitudes towards risk, which is important when making policy decisions regarding debt finance. Thus, CCC is a green responsibility and a financial strategy in contemporary corporate decision-making.

2.2. Climate Change Commitment and Debt Financing Policies

Stakeholder theory holds that companies are responsible to various stakeholders, not only shareholders, who determine company decision-making. In taking aggressive climate commitments, companies act in response to stakeholders, such as creditors, who might view environmentally committed companies as less risky borrowers, since such commitments signal regulatory compliance, long-term resilience, and reputational strength, thereby potentially improving debt access and reducing borrowing costs (Dzomonda, 2022). As per this theory, CCC influence debt financing policies by developing creditor trust through increased transparency, reduced environmental risk exposure and alignment with long-term value creation. It reduces the perceived default risk, encourages favourable lending terms, and enables firms to access capital at reduced costs while maintaining sustainable capital structures (Jangid & Sharma, 2025). Signalling theory also predicts that CCC is a good signal to the market that reflects good risk management, long-term focus, and operating transparency. These signals can make a firm more reputable, credit-worthy, and likely to secure better debt terms (Gahramanova & Kutlu Furtuna, 2023). Under signalling theory, CCC communicate plausible information regarding a firm’s high-risk management, sustainability orientation, and governance excellence. Such signals lower information asymmetry between the firm and lenders, promoting perceived creditworthiness, improving access to debt markets on better terms and at reduced borrowing costs (Birindelli et al., 2022). Trade-off theory, however, predicts that greater environmental commitments will raise operating expenses or create project risks, encouraging more conservative debt policies to preserve financial flexibility (Dang et al., 2023). CCC can decrease the risk of financial distress in the trade-off theory by increasing its costs through higher investments in sustainability and project risks that are not explicitly defined. To offset the tax benefit of debt against the increment of risks, more conservative leverage would allow companies to remain financially flexible to address uncertainty related to environmental projects and long-term commitments (Jangid & Sharma, 2025). In this way, CCC may empower or restrain the debt financing, depending on the way the markets interpret the costs, benefits, and reliability of the promises of the firm.

(Lemma et al., 2021) examined the effect of CCC and climate risk on debt financing policies on S&P 500 firms in 2015-2019. The results of this study revealed that the companies that have greater commitment to climate change activities have a higher debt proportion with extended maturity term. However, climate risk did not significantly impact debt financing policies. Although the study has specific merits, it is limited in its context of considering only data till 2019 and not considering any moderating role. Furthermore, the study of (Palea & Drogo, 2020) evaluated the relationship between carbon emissions and cost of debt financing for the sample of firms from the Eurozone from 2010 to 2018. There is a positive relationship between carbon emissions and the cost of debt financing. Research conducted by (Zhao et al., 2024) analysed the relationship between climate change and firm debt financing costs using non-financial listed firms in China from 1990 to 2017. The study found the negative impact of climate change on debt financing.

Furthermore, the study of (Qiu et al., 2025) also evaluated the role of climate change on debt financing using data from A-Share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2007 to 2021. Climate risk, it has been discovered, is a strong suppressive factor of corporate debt financing which operates both in the long-term and short-term debt financing. Moreover, (Trinh et al., 2024) examined the correlation between climate change exposure and the cost of debt in a sample of 21 European countries during the period of 2001-2020. The researchers established a positive effect of climate change exposure on cost of debt where the higher the exposure the higher the cost of debt. CCC in the stakeholder theory is an indicator of attentiveness to the interests of creditors, investors, regulators, and the society, and therefore a rise in trust and legitimacy (Pankratz, 2023). Such trust reduces the perceived risk of lenders so that they may lend more and offer better terms. Signalling theory also supports this relation by stating that CCC conveys credible information about good governance, risk management and long-term strategic orientation (Gahramanova & Kutlu Furtuna, 2023). Such good signals reduce the information asymmetry between the firm and lenders, which increases access to the debt market. Therefore, it is hypothesised that;

H1: Climate change commitment significantly and positively impacts debt financing policies.

2.3. Moderating Role of Institutional Investor

Relying on agency theory, institutional investors serve as monitoring agents that align managerial actions with shareholder interests and curb agency conflicts (Zhao et al., 2021). When firms commit to climate-related objectives, institutional investors can reinforce the credibility of these commitments. By pressing for transparency, accountability, and long-term value creation, these investors can further enhance these commitments (Paseda & Okanya, 2020).

From an agency theory point of view, institutional investors moderate the CCC–debt relationship by alleviating agency tension and reconciling managerial behaviour with shareholder and creditor interests. Their monitoring, transparency requirements, and insistence on ESG compliance minimise information asymmetry, improving the credibility of climate commitments. This credibility reduces lenders’ perception of environmental initiatives as financial risks rather than value-enhancing strategies (Zhao et al., 2021). Therefore, creditors are more likely to provide conducive debt terms since institutional supervision guarantees sound governance and prudent risk management. Institutional investors, therefore, play the role of credibility enhancers, with CCC assuring that it facilitates sustainability goals and optimal debt financing policies.

Within debt financing, the participation of institutional investors can reassure creditors that the firm is environmentally and financially responsible. By insisting on strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices and actively monitoring firms, institutional investors can assure creditors that a company’s climate pledges are genuine and supported by effective governance and risk management systems (Kordsachia et al., 2022). This, in effect, could lower perceived credit risk and facilitate better access to debt capital or even more effective loan conditions.

On the other hand, without robust institutional monitoring, lenders might doubt the genuineness or efficacy of a company’s CCC programs and consider them expense burdens that enhance financial risk (Ferreras et al., 2024; Lee & Choi, 2021). Institutional investors are therefore a trust-building device, which sustains the beneficial influence of CCC on debt financing policies and enables companies to attain both sustainability and financial goals (Chen et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025). Hence, it is hypothesised that;

H2: Institutional Investors significantly moderate the relationship between climate change commitment and debt financing policies.

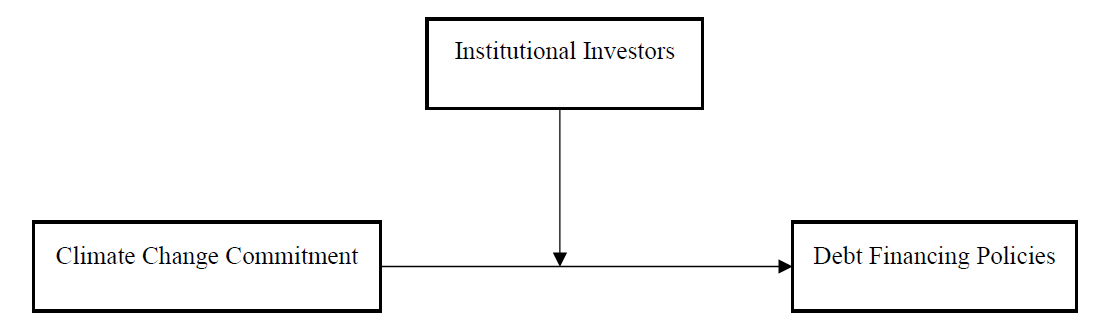

2.4. Conceptual Framework

Fig. (1) represents the conceptual framework of the study. The conceptual model examines the interaction between CCC as the independent variable and debt financing policies as the dependent variable, with institutional investor influence as a moderating variable. The model argues that companies with high CCC would realign their debt policies in response to perceived ecological risk or rising sustainability investment requirements (Lemma et al., 2021). Institutional investors can reinforce or weaken this link by affecting managerial choices, improving transparency, and boosting lender confidence (Zhao et al., 2021). Institutional investors function as active monitors and ensure that CCC efforts are credible and strategically aligned, potentially improving firms’ access to and terms of debt financing.

Fig. (1). Conceptual framework.

3. METHOD

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

This research targets 150 firms drawn from the S&P 500 index, employing a stratified sampling method for market capitalisation. The S&P 500 firms were divided into five groups according to the following thresholds of market capitalisation: Group 1 (Mega-cap: $87,500.30 – $3,900,000.00 billion), Group 2 (Large-cap: $25,500.34 – $87,500.29 billion), Group 3 (Upper mid-cap: $7,320.76 – $25,500.33 billion), Group 4 (Lower mid-cap: $1,450.51 – $7,320.75 billion), and Group 5 (Small-cap: $4.03 – $1,450.50 billion). From each group, 30 firms were randomly selected, ensuring proportional representation across firm sizes and reducing potential sampling bias. Hence, a total of 150 firms were used for the analysis.

Stratified sampling by market capitalisation was used to represent companies of different sizes proportionally to reduce the risk of size bias in the analysis. The allocation to firms by strata was fixed to ensure that groups were comparable on a balanced basis, irrespective of the natural distribution in the S&P 500. Although proportional representation would reflect the index’s composition more realistically, the method adopted optimises analytical comparability between firm sizes, allowing for easier detection of possible size-related patterns in commitment to climate change and debt financing practices. This method also reduces the risk that large-cap companies disproportionately influence results.

However, the study has certain limitations. One limitation is that the rigid assignment of 30 firms for each market capitalisation category is not the size distribution in the S&P 500, which could decrease external validity. Stratified sampling makes comparative analysis more feasible, but can overestimate smaller firms and undercount mega-cap firms compared to their actual market influence. Market capitalisation cut points are rigid and ignore time-series changes that might affect firm categorisation. Exclusion of companies beyond the S&P 500 restricts generalisability to broader markets. Random sampling within strata can still leave out sectoral heterogeneity, potentially excluding industry-specific differences in CCC and debt financing practices.

The time frame of the analysis ranges from 2010 to 2024, offering an all-embracing perspective of how CCC and debt financing policies have developed over time. This 15-year period permits observation of long-term trends and structural developments in corporate sustainability and financial strategies. This period captures primary regulatory shifts, enhanced climate disclosure mandates and rising investor pressure, providing a comprehensive view of evolving corporate sustainability and debt financing strategies post-global financial crisis.

Data were mainly gathered from companies’ annual reports, which yielded disclosures of climate change, sustainability practices, and institutional ownership information. Furthermore, Refinitiv Eikon was employed to calculate the financial ratios. Employing a dual-source method ensured the accuracy and reliability of the data and facilitated vigorous empirical testing of the research model.

3.2. Variables and Measurement

Table 1 shows the measurement of the related variables. The independent variable, CCC, is measured as a dummy variable (1 = disclosure; 0 = non-disclosure) using company annual reports. This binary measure identifies whether companies actually acknowledge and report their climate strategies. Disclosure is identified using predefined criteria, including emission targets, adaptation plans, mitigation initiatives, governance structures, and climate-related risk assessments, as outlined in company annual reports. For emission targets, it takes the value of 1 if firms have set a target to reduce emissions and 0 otherwise.

Table 1. Variable measurement.

| Variable | Measurement | Source | References |

| Independent Variable | |||

| Climate change commitment | Dummy Variable: 1 if the company discloses its CCC, while 0 if not. | Annual Report | (Abu Khalaf et al., 2025) |

| Dependent Variable | |||

| Debt Financing Policy | Debt to Equity: Debt divided by Equity | Reuters | (Lemma et al., 2021) |

| Debt Ratio: Debt divided by Assets | (Jawadi et al., 2025) | ||

| Interest coverage ratio: EBIT/Interest Expense | (McCoy et al., 2020) | ||

| Moderating Variable | |||

| Institutional Ownership | Percentage shares owned by banks | Annual Report | (Cheng et al., 2022) |

| Control Variables | |||

| ROA | Net profit divided by Total Assets | Reuters | (Ali et al., 2023) |

| ROE | Net profit divided by Total Equity | (Al Frijat et al., 2025). | |

| Market Capitalisation | Share Price*No of outstanding shares | (Lemma et al., 2021). | |

| Dividend Yield | Dividend per share is divided by price per share. | (Chandra & Sholihin, 2022). | |

| Firm Size | Ln (Total Assets) | (Lemma et al., 2021). | |

Furthermore, if the company has developed adaptation plans, it takes the value of 1; otherwise, it takes the value of 0. For governance structures, one was assigned if it disclosed a formal governance framework for climate change and 0 otherwise. For climate-related risk assessment, the value of 1 was given where there was disclosure on the risk assessment on climate change and zero otherwise. The final value of CCC was assigned 1 when at least 2 of the characteristics were present and 0 when there was 1 or 0 disclosure. These were adopted from the study of (Abu Khalaf et al., 2025).

Dependent variable, debt financing policy, is fully captured by three financial metrics: Debt to Equity (Lemma et al., 2021), Debt Ratio (Jawadi et al., 2025), and Interest Coverage Ratio (McCoy et al., 2020). Collectively, they measure a firm’s debt reliance, sustainability of debt, and capability to service interest, providing an informed understanding of debt policy. The moderating factor, institutional ownership, is the proportion of bank-held shares (Cheng et al., 2022) and may vary the impact of climate commitment on financing choices. Institutional ownership might either make firms adopt sustainable processes or demand financial returns.

Control variables, ROA (Ali et al., 2023), ROE (Al Frijat et al., 2025), Dividend Yield (Chandra & Sholihin, 2022), Market Capitalisation and firm size (Lemma et al., 2021), explain firm profitability, market size, pay-out policy, and size. These variables enable the identification of the underlying relationship, which makes the model more explanatory and credible. Including ROA, ROE, Dividend Yield, Market Capitalisation, and Firm Size as control variables is necessary to capture firm-specific attributes that may affect debt policy and CCC relationships. ROA and ROE try to portray distinct dimensions of profitability, which may impact a firm’s ability to repay debt and credibility among creditors (Ali et al., 2023; Al Frijat et al., 2025). Dividend Yield captures payout policy, conveying financial health and possibly affecting investor attitudes (Chandra & Sholihin, 2022). According to (Lemma et al., 2021), Market Capitalisation and Firm Size capture the size and market position of firms, which can influence both access to funds and pressure from stakeholders to invest in sustainability. Controlling for these variables isolates the actual effect of CCC on financing outcomes by eliminating omitted variable bias, thus enhancing the regression model’s explanatory power, validity, and robustness.

3.3. Data Analysis

The study has adopted the panel regression analysis technique using STATA software. It involved first the analysis of the random and fixed effect model. However, these models were diagnosed with the issue of heteroscedasticity using Modified Wald Statistics and autocorrelation as suggested by Wooldridge. Hence, a feasible GLS model has been used to fix heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation issues. The following equation is developed;

DE = Debt to Equity Ratio

CCC = Climate Change Commitment

ROE = Return on Equity

ROA = Return on Assets

DY = Dividend Yield

FS = Firm Size

MCAP = Market Capitalisation

II = Institutional Investors

II*CCC = Interaction term for Institutional Investors and Climate Change Commitment

CR = Coverage Ratio

DR = Debt Ratio

i = Panel ID

t = time period

µ = Error term

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics providing information about the variables’ central tendency, dispersion, and spread in the dataset Institutional ownership possesses a low mean (0.230 or 23%) and standard deviation (0.020 or 2%), reflecting uniformity in ownership percentages across companies. CCC possesses a mean of 0.789, reflecting that around 79% of companies report climate commitments. Financial ratios are highly variable. The debt-to-equity and interest coverage ratios have high standard deviations (312.95% and 484.46 times, respectively) and extreme maximum values, reflecting strong outliers and extensive variation in capital structures and interest payment ability. Market capitalisation is highly dispersed, indicating significant differences in firm size. Similarly, ROA and ROE vary extensively, with certain firms having significant losses. Dividend yield and firm size also indicate vast variability, suggesting the presence of a highly diversified sample of firms.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| II (%) | 2,250 | 0.230 | 0.020 | 0.160 | 0.295 |

| CCC | 2,250 | 0.789 | 0.408 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| DE (%) | 2,250 | 77.863 | 312.952 | 0.000 | 7753.330 |

| CR (Times) | 2,250 | 61.255 | 484.461 | -5848.560 | 9048.000 |

| DR (%) | 2,250 | 14.511 | 20.053 | -10.584 | 118.330 |

| MCAP ($billion) | 2,250 | 98,164 | 260,440 | -10,533 | 3,900,000 |

| ROA (%) | 2,250 | 6.485 | 8.713 | -88.240 | 49.180 |

| ROE (%) | 2,250 | 37.142 | 438.819 | -437.870 | 18555.200 |

| DY (Times) | 2,250 | 2.327 | 13.385 | 0.000 | 627.140 |

| FS | 2,250 | 9.349 | 3.375 | 1.018 | 15.203 |

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 below provides the correlation analysis between the variables. Institutional ownership has weak associations with every variable, meaning minimal direct correlation, although it positively correlates with the interest coverage ratio at 0.0315. CCC is negatively related to debt-to-equity ratio (-0.1020) and debt ratio (-0.2313), implying that companies committed to climate policies have lower leverage. It also exhibits a moderate negative correlation with company size (-0.2998), suggesting that smaller companies are likely to make climate commitments public. The debt-to-equity ratio is moderately positively correlated with the debt ratio (0.3493) and ROE (0.1458), suggesting that more leveraged companies can earn higher returns on equity but assume greater risk. Interest coverage ratio is positively correlated with ROA (0.1303), which indicates that successful companies find it less challenging to meet interest expenses. Market capitalisation is positively associated with firm size (0.2803) and ROA (0.2868), as more profitable firms tend to have higher market value. ROA and ROE have a positive association (0.1080), reflecting some stability in profitability measures.

Table 3. Correlation analysis.

| II | CCC | DE | CR | DR | MCAP | ROA | ROE | DY | FS | |

| II | 1 | |||||||||

| CCC | 0.011 | 1 | ||||||||

| DE | 0.020 | -0.102** | 1 | |||||||

| CR | 0.032 | 0.033 | -0.027 | 1 | ||||||

| DR | 0.019 | -0.231** | 0.349** | -0.077** | 1 | |||||

| MCAP | 0.017 | -0.206** | 0.062** | -0.002 | 0.157** | 1 | ||||

| ROA | 0.023 | -0.041** | 0.047** | 0.130** | 0.173** | 0.287** | 1 | |||

| ROE | 0.004 | -0.059** | 0.146** | 0.002 | 0.099** | 0.040 | 0.108** | 1 | ||

| DY | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.015 | -0.001 | 0.011 | 0.005 | -0.018 | -0.002 | 1 | |

| FS | 0.027 | -0.300** | 0.131** | -0.064** | 0.306** | 0.280** | -0.058** | 0.021 | 0.021 | 1 |

Note: ** indicates significance at 5% level

4.3. Data Analysis

Table 4 below shows the variables’ normality. The Shapiro-Wilk test is used to evaluate the normality. It shows that the variables are not generally distributed except for the institutional investors, which indicates a normal distribution.

Table 4. Normality testing.

| Variables | Obs | W | V | Z |

| II | 2,250 | 0.999 | 0.775 | -0.650 |

| CCC | 2,250 | 0.998 | 2.534 | 2.375*** |

| DE | 2,250 | 0.193 | 1065.607 | 17.809*** |

| CR | 2,250 | 0.105 | 1181.376 | 18.073*** |

| DR | 2,250 | 0.759 | 318.757 | 14.726*** |

| ROA | 2,250 | 0.826 | 230.157 | 13.894*** |

| ROE | 2,250 | 0.034 | 1275.596 | 18.269*** |

| DY | 2,250 | 0.048 | 1256.378 | 18.230*** |

| FS | 2,250 | 0.860 | 184.361 | 13.327*** |

| MCAP | 2,250 | 0.837 | 214.802 | 13.718*** |

Note: ***: showing significance at 1%

Table 5 shows the analysis of the heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation for the models. The table confirms the presence of heteroscedasticity for all three models and autocorrelation for the debt and interest coverage ratios. It also affirms the absence of endogeneity issues in the dataset for any model.

Table 5. Diagnostic test.

| Model 1: Debt to Equity | Model 2: Debt Ratio | Model 3: Interest Coverage Ratio | |

| Heteroscedasticity | 2860000000*** | 40381767*** | 1280000000*** |

| Auto-correlation | 0.175 | 164.245*** | 9.297*** |

| Endogeneity | 2.099 | 2.322 | 2.119 |

Note: *** indicates significance at 1%, ** indicates significance at 5%, * indicates significance at 10%

Table 6 shows the regression analysis. In Model 1, CCC has a strong positive influence on the debt-to-equity ratio (β = 59.681, p = 0.000), meaning that greater CCC is related to greater leverage. Model 2 indicates no significant effect on interest coverage (β = -0.983, p = 0.139), implying no substantial short-term liquidity consequence. Model 3 indicates that CCC is positively and significantly correlated with debt ratio (β = 14.287, p = 0.000). The findings show that CCC impacts the debt-to-equity and debt ratios significantly and positively. However, it does not have any significant impact on the interest coverage ratio. Overall, the findings indicate that CCC positively and significantly influences the debt financing policies. The findings of the study support the previous research findings. The study of (Lemma et al., 2021; and Palea & Drogo, 2020) have a positive and significant impact on debt financing. However, the study findings are negated by the study of (Zhao et al., 2024), which indicated a negative impact of CCC and debt financing. The difference in the findings is due to the consideration of the country, where Chinese firms have different climate commitments and are not as widely involved in these practices as firms from the S&P 500. In Model 1, institutional investors significantly moderate this influence (B = -262.397, p = 0.000), implying that institutional investor presence moderates the dependence on debt in more committed firms. For model 2, institutional investors do not have a significant and moderating impact on the interest coverage ratio (B = 1.098, P = 0.707). For model 3, institutional investors have a significant moderating impact (B = -62.754, P-value = 0.000) on the debt ratio. The study has established a significant moderating effect of institutional ownership on the relationship between CCC and debt financing. The empirical studies in this context have been limited. However, this empirical study confirms that the agency theory explains this moderating role. Agency theory underlines that institutional investors are effective monitors, aligning managerial behaviour with stakeholder interests. The empirical result underpins literature arguing that institutional investors increase the credibility of CCC by upholding transparency and risk management (Paseda & Okanya, 2020; Zhao et al., 2021). Their presence diminishes perceived credit risk, allowing for improved financing terms, hence filling the gap between environmental responsibility and financial strategy.

Table 6. Feasible GLS regression.

| Model 1: Debt to Equity | Model 2: Interest Coverage Ratio | Model 3: Debt Ratio | |

| Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | |

| CCC | 59.681*** | -0.983 | 14.287*** |

| ROE | 0.051*** | 0.000 | 0.001*** |

| ROA | -0.126*** | 0.524*** | -0.002*** |

| DY | 0.036*** | 0.001 | 0.029*** |

| FS | -0.003 | -0.122*** | -0.018*** |

| MCAP | -0.013 | 0.462*** | 0.021*** |

| II | 262.002*** | -0.763 | 62.814*** |

| CCC*II | -262.397*** | 1.098 | -62.754*** |

| MCAP Group | |||

| Lower Mid-cap | -58.816*** | 1.726*** | -14.027*** |

| Mega-cap | -25.189*** | -1.203*** | 3.023*** |

| Upper Mid Cap | -58.385*** | 0.221 | -14.019*** |

| Small Cap | -58.821*** | 1.982*** | -14.166*** |

Abbreviations: CCC = Climate Change Commitment, ROE = Return on Equity, ROA = Return on Assets, DY = Dividend Yield, FS = Firm Size, MCAP = Market Capitalisation, II = Institutional Investors, CCC*II = Interaction Term of Climate Change Commitment and Institutional Investors.

Note: *** indicates significance at 1%, ** indicates significance at 5%, * indicates significance at 10%

Among control variables, ROE (β = 0.051, p = 0.000) and DY (β = 0.036, p = 0.000) are positive on leverage, whereas ROA is negative (β = -0.126, p = 0.000). All lower-mid, upper-mid, and small-cap companies have significantly lower debt-to-equity ratios than their large-cap counterparts. In Model 2, ROA is positively correlated (β = 0.524, p = 0.000), and FS and mega-cap status are inversely related to interest coverage. MCAP and DY are positively correlated with liquidity capacity. In Model 3, ROE, DY, and MCAP correlate positively with debt ratio, while ROA and FS correlate negatively. Smaller market cap groups uniformly have lower debt ratios than mega-cap companies. The findings indicate that while CCC is generally linked with higher leverage, institutional investors moderate this relationship. Control variables such as profitability, dividend policy and firm size also play a critical role in explaining debt structure variations across firms and market capitalisation tiers.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The results have significant implications for policymakers, firms, and investors. Regulatory authorities in the S&P 500 should promote or require climate-related disclosures, as CCC can impact financial decision-making, especially if backed by robust institutional controls. Raising the standards for transparency can enhance market discipline and investor confidence. Second, companies listed in the S&P 500 ought to appreciate the strategic importance of engaging institutional investors since their monitoring function increases the credibility of sustainability promises and can lead to better debt financing terms. Institutional investors also serve as a bridge between environmental accountability and financial sustainability, strengthening trust among creditors. Third, institutional investors that have invested in the S&P 500 can be designed to reward or incentivise them to include ESG considerations in their investment decisions, aligning all financial systems with sustainability objectives. Overall, the research endorses a more integrated policy approach where corporate finance and ESG commitments are not considered independently but as complementary factors for reaching long-term value and sustainability.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This research aimed to explore the effect of CCC on S&P 500 companies’ debt policies and test the moderating influence of institutional ownership. Findings demonstrate that CCC tends to be linked with greater leverage, whereas institutional investors heavily moderate such a relationship by diminishing debt reliance in highly committed companies. Profitability, dividend policy, firm size, and market capitalisation also shape debt structures. These agency-theory-based findings underscore institutional investors as effective monitors, improving CCC credibility and reducing perceived credit risk. The implications of this study are two-fold: managers need to engage actively with institutional investors to improve governance and signal commitment to sustainability, and policymakers need to encourage mandatory climate disclosures and ESG integration into investment processes. Financial institutions need to include institutional ownership as a mitigating risk factor while evaluating the creditworthiness of climate-aware companies. Such harmonisation can enhance financing conditions and facilitate sustainable business strategies.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION

Although this research offers a helpful understanding of the role of institutional ownership in moderating the relationship between CCC and debt financing, it has certain limitations. For instance, employing a dummy variable as a proxy for CCC might simplify the complexity of climate policies and their intensity. Future research can implement more subtle measures, including climate performance scores or emission reduction targets. Second, the empirical analysis covers only a specific period and market situation, which could influence the applicability of the results across different nations or industries. Third, although the study controls for key financial factors, it does not explicitly address macroeconomic or policy factors that can influence both CCC and financing choices. Furthermore, research should investigate longitudinal designs to determine causal relationships over time and examine industry-specific dynamics. In addition, qualitative research might provide a richer understanding of how institutional investors shape sustainability practices beyond quantitative surveillance.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

W.R. has contributed to conceptualisation, idea generation, problem statement, methodology, results analysis, results interpretation, writing – original draft.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data will be made available at a reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author [W.R.].

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

REFERENCES

Abu Khalaf, B., Alqahtani, M. S., & Al-Naimi, M. S. (2025). Climate change commitment and stock returns in the gulf cooperation council (GCC) countries. Sustainability, 17(11), 5008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115008.

Ahmed, R. I., Zhao, G., Ahmad, N., & Habiba, U. (2022). A nexus between corporate social responsibility disclosure and its determinants in energy enterprises. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 1255–1268. 10.1108/JBIM-07-2020-0359.

Al Frijat, Y. S., Al‐Msiedeen, J. M., & Elamer, A. A. (2025). How green credit policies and climate change practices drive banking financial performance. Business Strategy & Development, 8(1), e70090. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.70090.

Albitar, K., Al-Shaer, H. & Liu, Y.S., (2023). Corporate commitment to climate change: The effect of eco-innovation and climate governance. Research Policy, 52(2), 104697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104697.

Ali, K., Nadeem, M., Pandey, R., & Bhabra, G. S. (2023). Do capital markets reward corporate climate change actions? Evidence from the cost of debt. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), 3417–3431. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3308.

Birindelli, G., Bonanno, G., Dell’Atti, S., & Iannuzzi, A. P. (2022). Climate change commitment, credit risk and the country’s environmental performance: Empirical evidence from a sample of international banks. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(4), 1641-1655. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2974.

Bjørn, A., Lloyd, S., & Matthews, D. (2021). From the Paris Agreement to corporate climate commitments: evaluation of seven methods for setting ‘science-based’emission targets. Environmental Research Letters, 16(5), 054019. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/abe57b.

Boiral, O., Henri, J. F., & Talbot, D. (2012). Modelling the impacts of corporate commitment on climate change. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(8), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.723.

Bose, S., Lim, E. K., Minnick, K., & Shams, S. (2024). Do foreign institutional investors influence corporate climate change disclosure quality? International evidence. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 32(2), 322–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12535.

Cato, M. S. (2022). Sustainable finance: Using the power of money to change the world. Palgrave Macmillan; 1st Edition. p.147. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-91578-0.

Chandra, Y. A., & Sholihin, M. R. (2022). the influence of dividend yield on sales volume of sharia constituent shares jakarta islamic index 70. Assets: Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Akuntansi, Keuangan dan Pajak, 6(1), 33-38. https://doi.org/10.30741/assets.v6i1.841.

Chen, H. M., Kuo, T. C., & Chen, J. L. (2022). Impacts on the ESG and financial performances of companies in the manufacturing industry based on the climate change-related risks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 380, 134951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134951.

Chen, J., Guo, X., & Liu, R. (2025). ESG rating uncertainty and the cost of debt financing. International Journal of Finance & Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.3123.

Cheng, X., Wang, H. H., & Wang, X. (2022). Common institutional ownership and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Banking & Finance, 136, 106218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2021.106218.

Dang, V. A., Gao, N., & Yu, T. (2023). Climate policy risk and corporate financial decisions: Evidence from the NOx budget trading program. Management Science, 69(12), 7517-7539. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4617.

Dzomonda, O. (2022). Environmental sustainability commitment and access to finance by small and medium enterprises: The role of financial performance and corporate governance. Sustainability, 14(14), 8863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148863.

Ferreras, A., Castro, P., & Tascón, M. T. (2024). Carbon performance and financial debt: Effect of formal and informal institutions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(4), 2801-2822. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2709.

Flammer, C., Toffel, M. W., & Viswanathan, K. (2021). Shareholder activism and firms’ voluntary disclosure of climate change risks. Strategic Management Journal, 42(10):1850-1879. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3313.

Gahramanova, G., & Kutlu Furtuna, Ö. (2023). Corporate climate change disclosures and capital structure strategies: evidence from Türkiye. Journal of Capital Markets Studies, 7(2), 140-155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCMS-10-2023-0039.

Gu, X., An, Z., Chen, C., & Li, D. (2023). Do foreign institutional investors monitor opportunistic managerial behaviour? Evidence from real earnings management. Accounting & Finance, 63(1), 317–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.13015.

Hsueh, L. (2022). Do businesses that disclose climate change information emit less carbon? Evidence from S&P 500 firms. Climate Change Economics, 13(02), 2250003. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2010007822500038.

Jabbour, C. J., Seuring, S., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B., Jugend, D., Fiorini, P. D., Latan, H., & Izeppi, W. C. (2020). Stakeholders, innovative business models for the circular economy and sustainable performance of firms in an emerging economy facing institutional voids. Journal of Environmental Management. 264, 110416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110416.

Jangid, M. L., & Sharma, A. K. (2025). Corporate commitment to climate change action and carbon performance: evidence from Asia-Pacific firms. Asian Review of Accounting. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-10-2024-0328.

Jawadi, F., Rozin, P., & Cheffou, A. I. (2025). Climate change uncertainty and corporate debt relationship: A quantile panel data analysis. Journal of International Money and Finance, 154, 103320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2025.103320.

Klettner, A. (2021). Stewardship codes and the role of institutional investors in corporate governance: An international comparison and typology. British Journal of Management, 32(4), 988–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12466.

Kordsachia, O., Focke, M., & Velte, P. (2022). Do sustainable institutional investors contribute to firms’ environmental performance? Empirical evidence from Europe. Review of Managerial Science, 16(5), 1409-1436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00484-7.

Kotz, M., Levermann, A., & Wenz, L. (2024). The economic commitment to climate change. Nature, 628(8008), 551-557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0.

Le, T. T. (2022). How do corporate social responsibility and green innovation transform corporate green strategy into sustainable firm performance? Journal of Cleaner Production. 362:132228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132228.

Lee, S. Y., & Choi, D. K. (2021). Does corporate carbon risk management mitigate the cost of debt capital? Evidence from South Korean climate change policies. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 57(7), 2138-2151.

Lemma, T. T., Lulseged, A., & Tavakolifar, M. (2021). Corporate commitment to climate change action, carbon risk exposure, and a firm’s debt financing policy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(8), 3919–3936. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2849.

Littlewood, D., Decelis, R., Hillenbrand, C., & Holt, D. (2018). Examining the drivers and outcomes of corporate commitment to climate change action in the European high-emitting industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1437–1449. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2194.

McCoy, J., Palomino, F., Perez-Orive, A., Press, C., & Sanz-Maldonado, G. (2020). Interest coverage ratios: assessing vulnerabilities in nonfinancial corporate credit. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2779.

Mohy‐ud‐Din, K., Shahbaz, M., & Du, A. M. (2025). Corporate social responsibility and climate change mitigation: Discovering the interaction role of green audit and sustainability committee. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(1), 1198-1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.3011.

Mukhopadhyay, D., & Sarkar, N. (2021). Do Green and Energy Indices Outperform BSESENSEX in India? Some evidence on investors’ commitment towards climate change. International Econometric Review, 13(2), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.33818/ier.787620.

Ooi, S. K., Ooi, C. A., & Tan, M. F. (2024). Stakeholder Pressure and Climate Change Performance: The Role of CSR-Oriented Organisational Culture. Global Business & Management Research, 16(4). https://www.gbmrjournal.com/pdf/v16n4/V16N4-2.pdf.

Palea, V., & Drogo, F. (2020). Carbon emissions and the cost of debt in the eurozone: The role of public policies, climate‐related disclosure and corporate governance. Business Strategy and The Environment, 29(8), 2953-2972. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2550

Pankratz, N., Bauer, R., & Derwall, J. (2023). Climate change, firm performance, and investor surprises. Management science, 69(12), 7352-7398. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2023.4685.

Paseda, O. A., & Okanya, O. (2020). Climate change in the theory of finance. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev, 11, 29-46. DOI: 10.7176/JESD/11-18-04.

Qiu, X., Zhuang, Y., & Liu, X. (2025). Climate risk and corporate debt financing: evidence from chinese a-share-listed firms. Sustainability, 17(9), 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093870.

Shi, J., Yu, C., Li, Y., & Wang, T. (2022). Does green financial policy affect the debt-financing cost of heavy-polluting enterprises? An empirical evidence based on Chinese pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 179, 121678.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121678.

Tavakolifar, M., Omar, A., Lemma, T. T., & Samkin, G. (2021). Media attention and its impact on corporate commitment to climate change action. Journal of Cleaner Production, 313, 127833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127833.

Trinh, V. Q., Trinh, H. H., Li, T., & Vo, X. V. (2024). Climate change exposure, financial development, and the cost of debt: Evidence from EU countries. Journal of Financial Stability, 74, 101315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2024.101315.

UCLA (2025). The State of Corporate Sustainability Disclosure 2025. Retrieved from: https://www.ioes.ucla.edu/project/the-state-of-corporate-sustainability-disclosure-2025/.

Xhindole, C., & Tarquinio, L. (2024). Determinants of companies’ commitment to climate change: Evidence based on European listed companies. Journal of Public Affairs, 24(3), e2938. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2938.

Xu, A., Su, Y., Wang, Y., & Liao, J. (2025). Carbon information disclosure and corporate financial performance—Empirical evidence based on heavily polluting industries in China. PloS one, 20(1), e0313638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0313638.

Yahaya, O. A. (2025). The role of institutional investors in the nexus between sustainability disclosure and firm performance. Available at SSRN 5171577. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5171577.

Yang, Z., Su, D., Xu, S., & Han, X. (2024). Institutional investors and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Pacific Economic Review, 29(2), 230-266. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12440.

Zhao, J., Qu, J., & Wang, L. (2021). Heterogeneous institutional investors, environmental information disclosure and debt financing pressure. Journal of Management and Governance, 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-021-09609-2.

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Dong, L., Sun, Y., & Zhang, N. (2024). The effect of climate change on firms’ debt financing costs: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 434, 140018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140018.

Zhou, Z., & Zhong, S. (2025). Impact of legal commitments on carbon intensity: A multi-country perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 373, 123696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123696.