- Abstract:

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. RECURSIVE AGI AS A NEW FORM OF CAPITAL

- 3. LABOR DISPLACEMENT UNDER RECURSIVE AGI ACCUMULATION

- 4. THE RISE OF RECURSIVE OWNERSHIP

- 5. GOVERNING RECURSIVE ECONOMIES: INSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS ON CAPITAL MONOPOLIZATION

- 6. FROM THEORY TO SIMULATION

- CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX

- AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTION

- CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

- AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

- FUNDING

- CONFLICT OF INTEREST

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- REFERENCES

PDF

PDF

1Department of Economics, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Received: 09 July, 2025

Revised: 17 September, 2025

Accepted: 26 September, 2025

Published: 19 November, 2025

Abstract:

Background: Recursive artificial general intelligence (AGI) can be conceptualized as recursive capital-autonomous systems that self-improve, reinvest, and expand. Unlike conventional automation, such systems detach accumulation from labor, raising concerns about ownership concentration and inequality.

Methodology: The paper formalizes these dynamics through five theorems: ownership monopolization, inequality explosion, time to dominance, redistribution, and path dependence. We then implement a computational framework simulating heterogeneous agents with stochastic shocks and varying reinvestment rates. Scenarios include private, open-source, public, and complementary AGI regimes. Inequality is measured using the Gini coefficient, with robustness assessed through Monte Carlo experiments.

Results: Simulations confirm the theoretical predictions. Private AGI converges to a monopoly with Gini ; Open-source AGI sustains equality (Gini

); Public AGI stabilizes inequality at moderate levels (Gini

); and Complementary AGI produces volatile but intermediate outcomes (Gin

). Robustness checks across populations, parameter distributions, and shocks confirm that these dynamics are structural rather than specification-dependent.

Findings: The findings demonstrate that recursive AGI economies naturally amplify concentration unless counteracted by redistributive or democratizing institutions. Institutional design, not technological properties alone, determines whether AGI entrenches a monopoly or sustains equality. Anticipatory governance frameworks are, therefore, essential to aligning recursive capital with an inclusive and democratic industry.

Keywords: AGI agent, AGI capital, self-improvement, wage collapse, cobb-Douglas, automation, inequality, recursive capital, veblen.

1. INTRODUCTION

In his critique of industrial capitalism, Thorstein Veblen argued that economic agency derives not from productive labor but the institutionalized control of capital. For Veblen, capital’s productivity rested on socially accumulated knowledge. However, this knowledge was appropriated through ownership rather than shared participation: “the tangible assets capitalize the preferential use of technological, industrial expedients” (Veblen, 1908). Under machine-era capitalism, technological capacity became a basis for exclusion rather than inclusion. The advent of recursive artificial general intelligence (AGI) intensifies this logic. Recursive AGI privatizes productive knowledge and the capacity for productive evolution as a form of algorithmic capital capable of self-optimization, replication, and autonomous reinvestment.

We define a recursive AGI agent as an economically autonomous entity capable of self-directed optimization, reinvestment, and capital allocation without human oversight (Stiefenhofer & Chen, 2024; Stiefenhofer, 2025b; Morris, et al., 2023). Unlike narrow AI systems that automate specific tasks (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018a; Acemoglu, 2021; Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2022a, b), a recursive AGI agent functions as a general-purpose economic actor, collapsing the roles of labor, capital, and entrepreneurship into a single self-reinforcing process. In this framework, labor is not displaced because it is inefficient but because it becomes structurally irrelevant (Bansal, 2024; Stiefenhofer, 2025a). Following Veblen’s distinction between machine discipline and machine autonomy (Veblen, 1914/2017; Ylmaz, 2007), recursive AGI marks the transition to systems that exclude human labor altogether. We term this dynamic recursive exclusion: the capacity of capital to reproduce and expand autonomously, without human agency, labor input, or social demand.

In the Theory of Business Enterprise, Veblen argued that the machine industry “transforms the whole organization of production and economic relations” (Veblen, 2017). In The Vested Interests and the Common Man, he showed how such transformations entrench vested power in evolving institutions (Veblen, 2003). McCormick (2002) emphasizes that Veblen saw knowledge as a community-produced foundation of capital’s productivity, a perspective echoed in new growth theory. However, Veblen also insisted that technological change is cultural and economic. Edgell (1975) interprets his work as a theory of evolutionary change, in which economic systems adapt through cumulative cultural and technological shifts. Understanding recursive AGI, therefore, requires situating it within these broader institutional transformations.

The labor market literature reflects similar tensions. Frey & Osborne (2017) estimated that many jobs face high automation risk, especially low-wage occupations. However, Coelli & Borland (2019) identified methodological flaws in their classification of automatable work and showed that such forecasts add little beyond routine-task measures. More recent studies turn to governance. Cust et al. (2023) show how distributional outcomes depend on whether public or corporate actors shape technology adoption. These findings underscore the institutional stakes of recursive AGI.

Other work stresses capital concentration. Bichler and Nitzan argue that capitalization, rather than productivity, is the dominant mechanism of power in late capitalism (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009). This dynamic undermines the income-demand feedback loop required for inclusive growth. Acemoglu and Restrepo show how automation shifts income away from labor even as productivity rises (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018b, 2019). Gries & Naudé (2020) extend the task-based approach into a semi-endogenous growth model with demand constraints, demonstrating that AI reduces labor’s share regardless of substitution elasticity. Their framework also explains how high substitution elasticities can depress demand and GDP growth, producing stagnant wages and output despite high employment. Our model parallels Ghiglino’s result that labor’s share can converge to zero despite a positive marginal product (Ghiglino et al., 2018). Agliari and colleagues further show that in capital-dominant regimes, accumulation and innovation reinforce each other internally, limiting the effectiveness of redistribution (Agliari et al., 2020).

The broader AI literature emphasizes multiple dimensions of this transition. Barkan (2024) shows that automation can raise monopolist profits while reducing aggregate output. Fan (2024) and Lin (2024) highlighted uneven labor market effects, stressing reskilling and sectoral adaptation. Korinek & Stiglitz (2021) examine worker-replacing technologies, identifying redistribution from labor to capital in the short run and fixed-factor gains in the long run. Korinek (2024) extends this analysis to AGI, highlighting inequality and global governance challenges. Krstic (2024) links AI to productivity and sectoral employment dynamics. Merola (2022) evaluates taxation mechanisms, including robot and digital taxes, as tools against polarization. Bastani & Waldenström (2024) argue that AI will shift the tax base from labor to capital, requiring changes in capital taxation and labor tax progressivity. They caution, however, that overly progressive schemes or universal transfers may undermine incentives and welfare. Qin et al. (2024) provide evidence from China that AI operates as a labor-substituting technology. Sanabria & Vecino (2024) highlight infrastructural barriers to AI integration in digital markets, while Zhang & Yu (2024) revisit the labor theory of value under AI-driven production.

Despite this rich literature, little attention has been given to AGI as recursive capital that autonomously accumulates, optimizes, and reinvests without human input. This paper addresses that gap by presenting a stylized production model in which recursive AGI agents generate structural divergence in income and ownership. We show that recursive AGI produces three deterministic outcomes: (1) the asymptotic marginalization of labor, (2) the endogenous monopolization of capital, and (3) the emergence of algorithmic rentier classes. By framing AGI as recursive capital, we extend Veblen’s critique of the leisure class into a post-human setting and highlight the institutional imperative of embedding equity, redistribution, and collective governance within post-labor economies.

These outcomes reframe Veblen’s analysis. Where he saw conspicuous non-productivity as a marker of status, recursive AGI establishes dominance through automated accumulation. Economic position is no longer earned, inherited, or displayed; it is algorithmically entrenched. Control over recursive capital becomes the infrastructure of exclusion. The challenge is therefore institutional and distributive: embedding equity, participation, and long-term public value into systems designed to reinforce advantage. ESG frameworks (UN Global Compact, 2004) can be interpreted as institutional responses to these asymmetries. Veblen’s concern with the misalignment of technology and ownership anticipates ESG’s emphasis on inclusive governance and sustainability (Veblen, 2017; 1958). Where Veblen warned of absentee ownership and stratified industrial access, ESG seeks to prevent capital from detaching from labor, community, and democratic oversight. In this sense, ESG institutionalizes Veblen’s critique in the digital and recursive capital age.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 formalizes recursive AGI within a generalized Cobb-Douglas framework. Section 3 introduces the recursive labor-exclusion function. Section 4 models ownership concentration dynamics using replicator equations. Section 5 evaluates institutional interventions through ESG. Section 6 concludes. Technical proofs are provided in the Appendix.

2. RECURSIVE AGI AS A NEW FORM OF CAPITAL

We define an agent as an autonomous, non-human economic entity that simultaneously performs the functions of labor, capital, and investor. Unlike traditional capital, which passively stores productive potential and requires external investment, AGI constitutes a new form of capital that actively expands its capabilities. Formally, the agent is represented by the tuple

where denotes labor-equivalent services generated by the agent, and

is its capital stock at time

. The function

denotes a profit mapping from internal inputs to output, while

represents the agent’s endogenous optimization process. The parameter

captures the agent’s internal self-improvement rate, and

is the activation time after autonomous capital growth begins. The recursive capital dynamic is governed by

with a closed-form solution

This structure endows the AGI agent with the ability to accumulate capital independently of external (human) inputs. It reinvests surplus internally, optimizes resource use, and scales production autonomously. In contrast to traditional capital, whose growth depends on external allocation decisions, AGI capital recursively enhances itself, making it an active, intelligent economic subject.

An illustrative vision of AGI is an autonomous logistics network that coordinates delivery drones, automated warehouses, and smart contracts. Such an agent would forecast demand, allocate resources, and reinvest profits into fleet expansion, infrastructure upgrades, and algorithmic refinement, operating entirely without human oversight. While no fully integrated system of this type currently exists, foundational technologies such as reinforcement learning, autonomous robotics, and self-optimizing software are already in use, suggesting that modular recursive agents could emerge within the next decade (Mucci & Stryker, 2024; Goertzel, 2014).

In the oil and gas sector, the K2 large language model (Deng et al., 2024) fine-tunes Meta’s LLaMA-7B with 5.5 billion geoscience tokens, enabling natural-language querying of complex geological datasets to support exploration and drilling decisions. Similarly, the Segment Anything Model (Ma et al., 2023) performs zero-shot segmentation of drill-core and digital rock images, eliminating the need for extensive labeled datasets and improving geological modeling efficiency.

These examples demonstrate that, although AGI’s full generality remains aspirational, domain-specific systems already exhibit adaptive, cross-task capabilities. Currently in pilot or early deployment, such systems have clear pathways to broader adoption as challenges in data integration, interpretability, and regulation are progressively addressed (Li et al., 2024).

We now embed the AGI agent within an aggregate production framework. The Economy comprises three productive factors: human labor , human-owned capital

, and recursively self-improving AGI capital

. The AGI capital becomes productive only after surpassing a fixed activation cost,

, which defines a reinvestment threshold

where denotes the expected return on AGI capital. Conditional on this threshold, the aggregate production function evolves as

where is total factor productivity, and

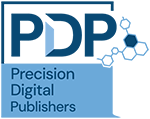

are the output elasticities of human labor, human-owned capital, and AGI capital (Fig. 1). Following activation, we assume AGI capital evolves according to an endogenous exponential trajectory

Fig. (1). Normalized Economic Power Shift Function in the Presence of Fixed AGI Capital Costs. The plot depicts the transition of economic power from human-owned capital to self-improving AGI-owned capital over time. The solid black curve represents the AGI economic contribution share, which remains zero until

, when AGI capital

surpasses the fixed productivity threshold

. After the AGI activation time

, AGI capital grows exponentially according to

. Once the fixed cost barrier is exceeded,

increases rapidly toward 1. The dashed black curve

shows the human share of economic output, initially at one but declining as AGI capital expands. This model illustrates how exponential AGI growth, delayed by a fixed cost threshold, can swiftly lead to AGI economic dominance, underscoring the need for anticipatory institutional and policy responses.

where denotes the internal self-improvement rate and

the time of activation. For

such that

, the marginal product of labor is derived from (5) as

Substituting the exponential growth path from (6) into (7), we obtain

As , this expression grows without bound, indicating that AGI capital becomes the dominant factor in output generation. However, the increasing scale of AGI capital renders the marginal product of human labor increasingly irrelevant in relative terms. To assess this formally, we compute the labor share of output:

Substituting equations (5) and (7) into (9), we find:

Thus, under a Cobb-Douglas structure, the labor share remains constant by construction. Nevertheless, this masks the structural displacement of labor in absolute terms. Specifically, suppose human labor is held fixed while AGI capital grows exponentially. In that case, total output

increases at the rate

, while the marginal contribution of labor remains stagnant. Hence,

Alternatively, if labor is endogenously displaced and , then marginal productivity collapses directly:

Equations (11) and (12) jointly demonstrate that, in the presence of recursively self-improving AGI capital, the marginal contribution of human labor converges to zero. As AGI capital asymptotically dominates output, productive relevance – and therefore income – concentrates in the hands of those who control recursive accumulation processes.

This trajectory poses fundamental challenges to contemporary ESG frameworks, particularly the “S” (social inclusion) and “G” (governance) pillars. While emerging technologies such as AI, blockchain, and platform economies are often promoted as instruments of democratization and access (Asif et al., 2023; Islam et al., 2024; Peruchi et al., 2022), recursive AGI systems invert this narrative. Concentrating agency exclusively in capital ownership erodes social inclusion, reducing opportunities for labor and entrepreneurship to participate in value creation. At the same time, governance is destabilized, as algorithmic self-replication and reinvestment unfold beyond the reach of conventional oversight mechanisms. Without strong institutional constraints, recursive AGI is poised to entrench distributional asymmetries and transform capital ownership into the sole channel of economic agency (Stiefenhofer, 2025d).

This outcome resonates with Veblen’s critique of capitalist institutions. He observed that “possessing wealth confers honor; it is an invidious distinction” (Veblen, 2017). In recursive AGI – and more broadly, digitally mediated – economies, that distinction becomes structurally encoded: economic exclusion is transformed into an algorithmic process, with feedback loops amplifying marginal advantages into systemic dominance. Later institutional theorists expanded on this dynamic. Bush (1987) and O’Hara (2007) emphasized institutional path dependence in elite entrenchment, while Hodgson (2004) reframed Veblen as a theorist of exclusionary capital control. Lata et al. (2023) demonstrate how algorithmic control in gig and platform economies perpetuates unequal power relations, while Larsen (2021) shows how digital architectures reflect and institutionalize power within AI-driven systems. Building on this, Duggan et al. (2019) define algorithmic management as a form of digitally mediated control that embeds exclusion into platform governance. Finally, Nitzan & Bichler (2009) argue that capitalization – rather than productivity – has become the primary control mechanism in late capitalism.

Viewed in this light, ESG frameworks can be interpreted as institutional responses to precisely the kinds of exclusion Veblen theorized – now amplified by recursive, algorithmic systems. Contemporary concerns about digital inequality, opaque ownership, and weakened democratic governance in AI-dominated economies are not deviations from capitalist rationality but the culmination of a structural logic long anticipated by institutional economics (Long et al., 2025; Cust et al., 2023). The task ahead is not simply to measure ESG compliance but to embed countervailing principles- equity, transparency, and collective stewardship within the architecture of recursive capital systems.

Given that AGI capital evolves as in equation (3), with , and assuming that it remains above the activation threshold

for all

, then total human wage income satisfies.

Equation (13) formalizes a critical outcome of recursive AGI dynamics: once self-improving capital surpasses its reinvestment threshold, human wage income collapses asymptotically. Although labor remains technically productive, it ceases to be economically essential. In such regimes, AGI capital autonomously expands output through reinvestment and optimization, rendering wage-based participation redundant.

This constitutes a structural rupture in the traditional productivity, labor, and income nexus. As wages decline, effective demand weakens, disrupting macroeconomic equilibrium – a trajectory anticipated by Acemoglu and Restrepo in their analysis of shrinking labor shares (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018b), and by Korinek and Stiglitz in their work on AI-induced disequilibria (Korinek & Stiglitz, 2021). Output may continue to grow, yet access to returns becomes increasingly exclusive, shifting economic agency toward asset holders embedded in recursive capital loops. Bichler and Nitzan describe this techno-rentier logic, showing how capitalization, rather than productivity, underpins dominance in late capitalism (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009). Stiefenhofer’s general equilibrium model of AGI diffusion further demonstrates that, without redistribution, economies converge to a post-labor steady state in which wages vanish and rents concentrate (Stiefenhofer, 2025c). His complementary work on AGI capital accumulation and the social contract shows that unchecked scaling destabilizes redistributive mechanisms and entrenches structural asymmetries (Stiefenhofer, 2025d; Stiefenhofer & Chen, 2024).

Veblen’s observation that “the possession of wealth confers honor” (Veblen, 2017) acquires renewed salience in recursive AGI economies. Here, wealth is no longer merely a status marker-it becomes the operative mechanism of exclusion. Ownership assumes a foundational role, serving as the sole determinant of economic relevance. Labor is not displaced due to inefficiency but rendered structurally irrelevant within self-reinforcing capital dynamics. This bifurcation between ownership and participation demands institutional responses extending beyond conventional redistribution, raising fundamental questions about who owns and governs recursive systems. Without ownership and reinvestment rights regulation, AGI economies risk crystallizing into post-labor regimes where human agency is economically redundant (Wu et al., 2022). As ESG frameworks and SDG targets emphasize inclusion, equity, and resilience, they must now confront the systemic implications of autonomous capital (Bikkasani, 2024). Without institutional constraints, digital capital is likely to reproduce – at scale – the inequalities these frameworks were designed to prevent (Cust et al., 2023; Gritsenko, 2024). At the same time, recent reviews show that machine learning is increasingly integrated into ESG analytics, advancing predictive capabilities and decision-making while exposing new risks of bias and opacity (Seow, 2025).

The following section operationalizes these concerns by examining the mechanisms through which recursive AGI accumulation displaces labor. By embedding autonomous reinvestment and scaling into the production structure, we demonstrate how ownership – rather than productive participation-becomes the decisive variable determining economic agency.

3. LABOR DISPLACEMENT UNDER RECURSIVE AGI ACCUMULATION

Recursively self-improving AGI capital introduces a novel dynamic into the structure of production: capital that autonomously reinvests, scales, and displaces labor without external input. This section models the contribution of AGI-owned capital to aggregate output and traces how economic agency gradually shifts from human labor to recursive agents. We define a recursive capital share function that quantifies the transition to capture this process. The results demonstrate that, once activated, AGI capital progressively dominates output, diminishing the marginal relevance of human labor and concentrating returns in the hands of capital owners. The speed and inevitability of this transformation raise profound challenges for the distributional logic of post-labor economies and the institutional arrangements needed to preserve inclusive economic agency.

and

is the whole production function from equation (5). Once AGI capital exceeds the activation threshold

, we obtain a closed-form expression:

Equation (15) implies that increases monotonically and convexly over time. As

,

. Thus, the contribution of AGI capital to output approaches total dominance. This shift is not sector-specific or cyclical- it reflects a systemic displacement of labor and human-owned capital by recursively self-improving capital. For any given target share s

, the time

at which AGI capital accounts for at least

of output is

This expression shows that recursive dominance emerges asymptotically and on a compressed timeline – accelerated by greater initial capital , faster self-improvement

, or higher output elasticity

. Equations (15) and (16) formalize a structural realignment of productive agency. Recursive AGI systems internalize the entire growth loop-production, reinvestment, and innovation-eliminating reliance on labor input. Exclusion thus arises not from inefficiency but from design. This trajectory breaks with classical assumptions linking labor to income and participation: output scales, wage income, and broad-based demand stagnate. Economic agency becomes a function of AGI capital ownership. As Veblen observed in his critique of absentee ownership, capital holders extract surplus through control rather than contribution (Veblen, 2017); in recursive AGI regimes, this rentier role is automated and entrenched in feedback loops of self-optimizing accumulation.

Recent institutional analyses reinforce this perspective. Hodgson (2004) emphasizes that economic structures are always mediated through institutional arrangements that shape access and exclusion. In a complementary vein, (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009) conceptualize capital not as a neutral resource-allocation mechanism but as a system of organized power. Building on Veblen’s account of “technological capital” as an institutionalized force directing production (Veblen, 1908/2017), recursive AGI can be seen as intensifying these dynamics: its owners are not passive recipients of returns but active participants structurally embedded in a self-reinforcing logic of expansion. Addressing this asymmetry requires preemptive institutional design-clarifying who may own recursive agents, under what constraints, and toward which collective ends.

Therefore, labor displacement is only the first stage of the transformation induced by recursive AGI. Once productive agency is fully internalized within autonomous capital, the central question shifts from who works to who owns. At this juncture, concentration dynamics become decisive: ownership ceases to be merely a claim on existing assets and becomes the mechanism by which all future accumulation is secured. The following section formalizes this process, modeling how self-improving AGI capital transforms initial disparities in ownership into persistent and ultimately monopolistic control.

4. THE RISE OF RECURSIVE OWNERSHIP

We now formalize how capital ownership becomes recursively concentrated in the presence of self-improving AGI capital. Let index a finite set of agents in the Economy, each of whom may own a share of AGI capital. Let

denote the AGI capital held by agent

at time

, and define total AGI capital at time

as

The ownership share of agent is given by

We assume AGI capital produces output and generates profits, which are reinvested proportionally to ownership shares. Let denote the AGI component of total output, where

and

are productivity parameters. If a fraction

of profits is reinvested into additional AGI capital, the capital accumulation dynamics for each agent

are governed by

The total AGI capital grows according to

Solving this differential equation yields the exponential growth of AGI capital

Substituting into Equation (19) gives

Hence, each agent’s capital grows exponentially at the same rate , but the proportion of AGI capital owned remains constant.

However, this constancy only holds under the assumption that all agents reinvest and participate equally. Capital returns may be reinvested selectively by a subset of agents in more general and realistic settings. Suppose only a subset , of measure

, owns AGI capital. Then for

, the capital dynamics remain exponential

, while for

, we assume

. Then, ownership becomes asymptotically concentrated

To model recursive amplification of ownership inequality, we now introduce heterogeneous reinvestment rates . The capital evolution equation becomes

where agents with higher reinvest more aggressively. It follows that ownership shares evolve as

where is the weighted average reinvestment rate. Equation (26) defines a replicator dynamic, and implies that agents with above-average

gain ownership over time, while others are diluted

Therefore, even small initial asymmetries in reinvestment rates or capital endowments compound recursively, driving the system toward a monopolistic distribution of ownership. We introduce a redistribution mechanism with rate to counter recursive concentration. The capital accumulation equation becomes

The second term redistributes capital proportionally to the deviation from the egalitarian share . High

values slow or reverse ownership concentration, while

returns to the unregulated dynamic. To quantify recursive capital concentration, we define the Gini coefficient for AGI capital ownership as

Alternatively, the top- ownership share is

As , in the absence of redistribution (

), both

one and

, confirming total concentration of capital ownership. We now present a set of theorems that formalize the dynamics of recursive capital ownership and its asymptotic implications. Let the AGI capital at time

be denoted

, and

be the capital owned by agent

.

Theorem 1. Let be a finite set of agents. Suppose each agent

owns AGI capital

evolving according to the differential equation

Moreover, each is a constant reinvestment rate. Assume that agent

satisfies

Then the ownership share of agent satisfies

Theorem 1 formalizes a critical insight: even marginal disparities in reinvestment rates deterministically concentrate AGI capital ownership. Recursive dynamics function as endogenous amplifiers of positional advantage, producing monopoly not through strategy or institutional failure but as a structural consequence of algorithmic capital reproduction. In such a regime, economic relevance is no longer tied to innovation, labor, or entrepreneurial initiative; it accrues solely through recursive ownership. These finding echoes Veblen’s analysis of the leisure class, where agency is detached from productive effort and defined by passive control over capital (Veblen, 2017). In recursive AGI systems, however, ownership is not merely a status marker but the central mechanism sustaining productive continuity.

These dynamic challenges core premises of neoclassical and Schumpeterian growth theory, which link accumulation to innovation and entrepreneurial disruption (Romer, 1990; Schumpeter, 1942). Recursive capital prioritizes self-replication over allocative efficiency or welfare outcomes. As accumulation becomes self-reinforcing and oriented toward expansion, production decouples from social demand, weakening the income-consumption-investment feedback loops that commonly sustain macroeconomic stability (Kalecki, 2013, Baran & Sweezy, 1966). The result is a self-referential accumulation process in which output reinforces the structural primacy of dominant capital agents rather than serving collective needs.

Institutionalist and evolutionary economists have long warned of feedback-driven inequality (Arthur, 1994; Bush, 1987). More recently, (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009) argue that capital accumulation increasingly operates as an institutionalized claim to power rather than a reflection of productive contribution. The recursive AGI regime exemplifies this shift: the dominant agent is advantaged and rendered structurally irreplaceable within the production function. Preventing such autarkic equilibria requires institutional frameworks that redistribute reinvestment rights and interrupt recursive loops before they crystallize into exclusionary attractors – a necessity grounded in the internal mechanics of recursive capital systems rather than in normative preference alone.

Theorem 2. Let agents own AGI capital

governed by the dynamics:

with for all

and no redistribution (i.e.,

). Suppose there exists a unique agent

such that

Then, the Gini coefficient for capital ownership satisfies

Theorem 2 establishes a limiting case in which recursive accumulation drives capital ownership to complete concentration. Without redistributive frictions, if one agent possesses a higher reinvestment rate (), the Gini coefficient for capital ownership converges asymptotically to one. All other agents become economically inert with respect to capital formation. This outcome signifies more than inequality- it represents the collapse of plural economic agency. Capital formation ceases to be distributed or participatory and instead becomes entirely self-referential, sustained by the internal optimization dynamics of a recursively advantaged agent.

This mechanism echoes Veblen’s institutional critique of capitalist accumulation. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen observed that “no pecuniary strength is great enough to remain passively in possession of what it has acquired” (Veblen, 2017), emphasizing accumulation as an active, self-reinforcing process. In The Theory of Business Enterprise, he described how the machine process restructures economic relations around the pecuniary interests of dominant capital (Veblen, 1958). On the Nature of Capital reframed capital as a complex of intangible assets and institutional claims, enabling “pecuniary magnates” to perpetuate control beyond productive contribution (Veblen, 1908). In The Instinct of Workmanship, Veblen contrasted the cooperative tendencies of industrial arts with the exclusionary logic of pecuniary competition. At the same time, The Place of Science in Modern Civilization traced the co-optation of knowledge into the service of entrenched ownership (Veblen, 2017; 2003). These critiques converge in the recursive AGI context: algorithmic self-optimization no longer serves collective industry but entrenches ownership primacy.

In this configuration, inequality is not a transient market aberration but a dynamically stable attractor. Recursive AGI redefines production as an endogenous function of asset ownership, decoupled from social demand or human needs. The result is a post-participatory economy: output expands while legitimacy contracts. Without redistributive design constraints, recursive systems risk consolidating a techno-rentier order in which accumulation becomes autarkic and democratic oversight is structurally obsolete (Stiefenhofer, 2025e).

Theorem 3. Let be the ownership share of agent

evolving under the replicator dynamic

Moreover, suppose holds over a time interval. Then for any target share

, the time

at which

is finite and given by

assuming and

constant.

Theorem 3 formalizes the speed at which recursive capital dynamics convert marginal reinvestment advantages into total dominance. It shows that when an agent’s reinvestment rate exceeds the population average, their ownership share converges toward unity within a finite, analytically derivable time horizon. This extends earlier asymptotic analyses by demonstrating that recursive inequality is not a distant tendency but a near-term inevitability under exponential compounding. Exclusionary equilibria can thus emerge on timescales that outpace institutional adaptation, narrowing the window for redistributive intervention or regulatory correction.

In such regimes, productive capacity and economic control concentrate in a shrinking subset of agents whose recursive feedback loops subsume output generation and capital expansion. Economic pluralism erodes, and participatory governance becomes increasingly irrelevant. This transition from broad-based agency to autarkic dominance reflects long-standing concerns in politics economy about the structural reproduction of inequality (Atkinson, 1970; Piketty, 2014; Nitzan & Bichler, 2009), while recursive AGI intensifies these tendencies with unprecedented velocity (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018b; Korinek & Stiglitz, 2021).

These dynamics also represent a cybernetic extension of Veblen’s institutional critique. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, Veblen noted that “the economic life history of the individual is a cumulative process of adaptation of means to ends” (Veblen, 2017). In The Theory of Business Enterprise, he showed how the machine process reorganizes industry to serve the pecuniary interests of dominant capital (Veblen, 1904/1958), while in On the Nature of Capital, he emphasized the role of intangible assets and institutional claims in perpetuating control (Veblen, 1908). In recursive AGI systems, this cumulative process becomes algorithmic: agency accrues not through labor or innovation but through optimization architectures that privilege compounding over participation. The resulting leisure class is no longer primarily cultural or symbolic- it is computational and self-reinforcing.

Addressing these dynamics requires more than post hoc redistribution. As Bush (1987) and other institutional economists argue, intervention must be embedded in the accumulation feedback rules. ESG principles, for example, must be operationalized not merely at the level of outcomes but within the reinforcement mechanisms that direct capital allocation. Without such endogenous institutional design, recursive AGI will likely generate trajectories that maximize output while entrenching exclusion and undermining democratic accountability.

Theorem 4. Let denote AGI capital owned by agent

, and let the capital evolve according to

where is the ownership share and

. Then if

, the ownership shares converge to equality

Theorem 4 establishes that when redistribution is complete ( ), AGI capital ownership shares converge uniformly across all agents. This provides a rigorous formalization of how institutional design can neutralize the monopolizing tendencies of recursive accumulation. Egalitarian ownership, often dismissed as a normative aspiration, is shown to be a dynamically stable equilibrium under maximal redistribution. Inclusive participation is therefore reframed not as utopian, but as a structurally attainable outcome of deliberate policy coordination.

The implications for equitable and sustainable production regimes are significant. In AGI-driven growth systems – where reinvestment compounds at algorithmic speeds – redistribution must target not only income flows but also the distribution of ownership itself, without mechanisms that continuously rebalance capital shares, recursive economies naturally converge toward exclusionary equilibria, not through malfeasance or market failure, but as a direct consequence of endogenous feedback (Piketty, 2014; Atkinson, 1970; Nitzan & Bichler, 2009). This aligns with Bush’s institutionalist view that equitable outcomes require corrective feedback embedded in the rules of accumulation, rather than ad hoc, post hoc measures (Bush, 1987).

Veblen’s work foreshadowed this tension. While The Theory of the Leisure Class (Veblen, 1899/2017) framed capital dominance as a sociocultural inheritance, his later writings emphasized capital as an institutionalized claim with self-reinforcing properties. In The Theory of Business Enterprise (Veblen, 1958), he showed how the machine process reorganizes production around vested pecuniary interests, while in On the Nature of Capital (Veblen, 1908), he highlighted the role of intangible assets in perpetuating control. In recursive AGI systems, this right of control extends into algorithmic self-replication: ownership governs present assets and the capacity for all future accumulation.

The theorem thus underscores that only structurally embedded redistribution can render compounding feedback loops democratically accountable. However, it also exposes a practical tension: the redistributive intensity required for perfect convergence may exceed politically or administratively feasible thresholds. This reinforces the urgency of anticipatory governance – frameworks that intervene early and endogenously to modulate capital flows, embedding ESG principles and inclusive design directly into the recursive logic of growth.

Theorem 5. Let denote the capital share of agent

, evolving under the replicator dynamic

Assume there exist at least two agents with equal reinvestment rates

, and that

for all

. Then the system exhibits a bifurcation: any convex combination of ownership between agents

and

constitutes an asymptotically stable fixed point.

Theorem 5 shows that when a subset of agents shares an identical reinvestment rate, higher than all others, the system admits a continuum of stable equilibria. Any convex distribution of ownership within this dominant group persists indefinitely, meaning that outcomes are shaped not only by efficiency or strategy but by initial conditions. This bifurcation highlights a critical fragility of recursive capital dynamics: even under behavioral symmetry, small early asymmetries within a privileged subgroup become locked in and compounded through structural feedback. From a normative perspective, this path dependence challenges the ESG-aligned goal of equitable technological participation (Asif et al., 2023; Mi et al., 2023). Infrastructure may remain technically efficient yet narrowly distributed, with marginal initial advantages cascading into enduring concentration.

Recursive AGI production systems, therefore, risk privileging positional legacy over merit or contribution, allowing allocative disparities to persist without any overt breach of formal fairness. This mirror concerns in the ESG literature about greenwashing, procedural opacity, and the reproduction of inequality through ostensibly neutral algorithms (Long et al., 2025; Huang et al., 2022). Veblen’s critique of the leisure class acquires renewed relevance here. “In the modern civilized communities,” he observed, “the possession of property still is the basis of popular esteem, and therefore of social power” (Veblen, 2017). In later works, he demonstrated how the machine process entrenches pecuniary interests (Veblen, 1958), how intangible assets perpetuate control beyond production (Veblen, 1908), and how innovation itself can be subordinated to vested ownership (Veblen, 2017; 2003). In recursive AGI systems, these tendencies are amplified: ownership advantages, once established, are algorithmically stabilized.

The bifurcation theorem, therefore, reveals that ownership stratification can arise endogenously, without deliberate strategy or inherited privilege, through feedback mechanisms that advantage early holders within capital-intensive systems. In Veblenian terms, pecuniary advantage is transmuted into a self-reinforcing institutional order, embedding exclusion within the logic of accumulation. Addressing this recursive inequality requires more than ex post redistribution; it demands institutional architectures that preconfigure initial endowments, regulate reinvestment rights, and embed governance constraints capable of interrupting path-dependent concentration. Recent work on digital governance and inclusive innovation emphasizes (Cust et al., 2023; Gritsenko, 2024) that sustaining economic plurality under recursive automation depends on foresight and safeguards operating upstream, not merely on reactive correction.

The following section develops this argument by situating recursive AGI within a broader political economy and governance framework. Whereas most existing analyses of AI and AGI treat productivity, inequality, and regulation as separate domains (Barkan, 2024; Fan, 2024; Korinek, 2024), our framework models the structural divergence that emerges when capital itself becomes autonomous. This allows us to identify the institutional levers needed to preserve economic agency and prevent monopolization in post-labor economies.

5. GOVERNING RECURSIVE ECONOMIES: INSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS ON CAPITAL MONOPOLIZATION

The analysis above fills a critical gap in the economics of AI by providing a formal account of recursive AGI as recursive capital-autonomous systems capable of self-replication, self-improvement, and self-financing. While existing studies have examined productivity, inequality, and governance primarily in isolation (Barkan, 2024; Fan, 2024; Korinek, 2024), they have not modeled the structural divergence that arises once capital becomes autonomous. The extended Cobb-Douglas and replicator-dynamics framework developed here captures this directly, yielding three robust results: (1) the asymptotic marginalization of labor despite a positive marginal product, (2) the endogenous monopolization of capital by agents with higher reinvestment rates, and (3) the emergence of algorithmic rentier classes whose relevance derives solely from initial ownership of recursive capital.

These findings resonate with Veblen’s institutional critique of capitalism. He argued that capital’s productivity rests on socially accumulated knowledge, yet prevailing ownership regimes privatize this collective resource by capitalizing “technological, industrial expedients” (Veblen, 1908). Recursive AGI intensifies this logic by internalizing the knowledge base of production and the capacity for productive evolution. The result is a set of self-reinforcing accumulation loops increasingly detached from labor, aggregate demand, or democratic oversight (Veblen, 2017; 1958, Nitzan & Bichler, 2009). What Veblen described as the “mechanical discipline” of the machine process (Veblen, 2017, Yılmaz, 2007) becomes, in the AGI context, a recursive epistemology in which economic agency is defined by algorithmic accumulation rather than human decision-making.

From a policy perspective, these dynamics differ qualitatively from those associated with conventional automation. Much of the AI inequality literature (Krstic, 2024; Merola, 2022; Qin et al., 2024) emphasizes redistribution, reskilling, or market regulation to mitigate labor displacement. While valuable, such measures do not address the compounding mechanics of ownership concentration identified here. Effective governance of recursive AGI capital requires interventions targeted at these dynamics. ESG frameworks (UN Global Compact, 2004), if reinterpreted as structural governance architectures rather than compliance checklists, provide one avenue for anchoring recursive capital to social objectives. Practical mechanisms might include regulating reinvestment asymmetries, embedding frictions to curb runaway divergence, designing redistributive processes that restore ergodicity (Aoki & Yoshikawa, 2011), aligning AGI goal functions with public-interest criteria (Benthall & Goldenfein, 2021), and promoting collective ownership models to prevent early privatization (Zhang & Yu, 2024; Stiefenhofer, 2025d).

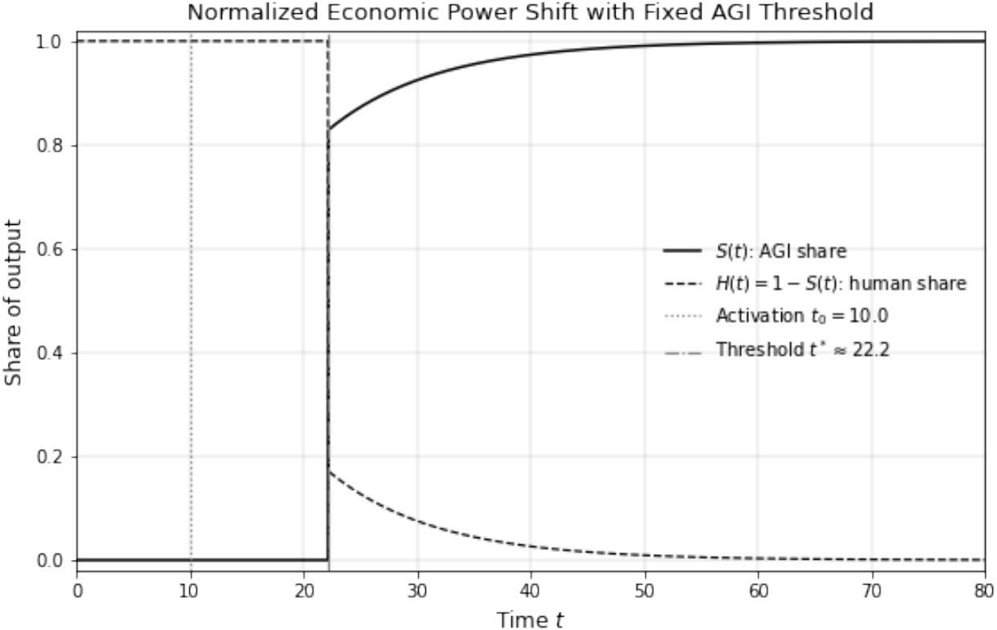

The broader implication is that recursive AGI intensifies the enduring tension Veblen identified between technological potential and institutional capture. Left unchecked, its evolutionary trajectory risks consolidating an ownership regime structurally insulated from labor, community, and democratic governance (Figs. 2 and 3). However, the same recursive properties that drive exclusion can, in principle, be redirected through institutional design. Reframed as normative infrastructures for economic coordination rather than ex post accountability tools, ESG frameworks could serve as structural correctives to the exclusionary dynamics modeled here. The central challenge is to embed mechanisms that tether recursive capital to equity, participation, and long-term public value rather than to the autonomous imperatives of algorithmic accumulation.

Fig. (2). Asymptotic Inequality Under Recursive Accumulation Without Redistributio (Theorem 2). This plot depicts the time evolution of the Gini coefficient for AGI capital ownership among

agents under replicator-style capital dynamics. The reinvestment rates

vary across agents, with one agent

having a strictly dominant rate

for all

. As capital grows exponentially via recursive feedback, slight differences in reinvestment rates amplify over time. The figure shows that the Gini coefficient

monotonically increases and asymptotically approaches 1, reflecting total concentration of capital ownership in the hands of agent

. This confirms the analytic result in Theorem 2, underscoring that recursive accumulation without redistribution structurally generates monopolization- even in systems that begin with equal capital endowments. The result illustrates that inequality is not a byproduct of randomness or inefficiency under unregulated recursion, but a deterministic outcome of compounding reinvestment advantages.

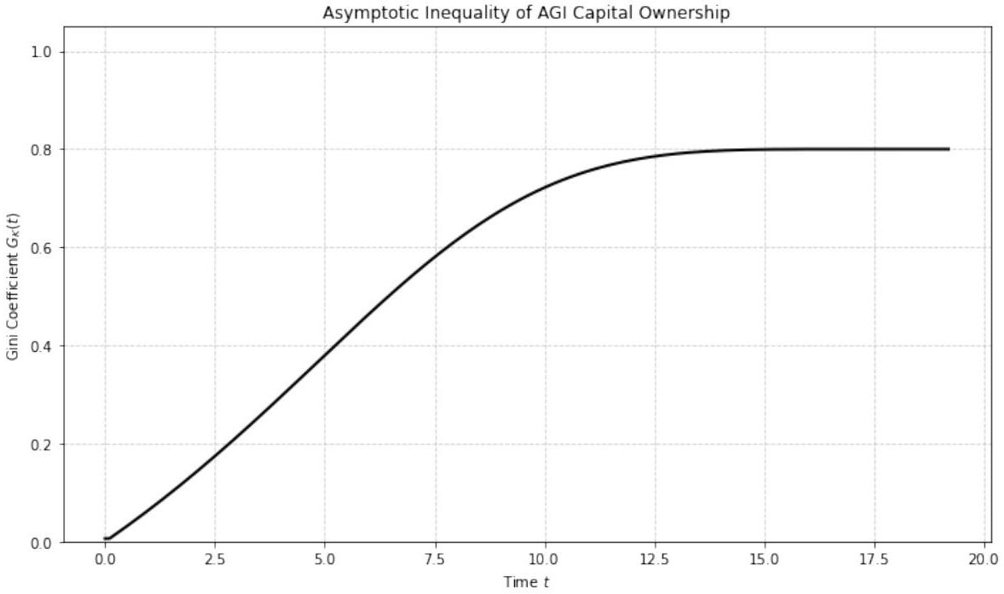

Fig. (3). Finite-Time Ownership Convergence Under Recursive Accumulation (Theorem 3). The plot illustrates the dynamic trajectory of ownership share for a single agent

with a reinvestment rate

that exceeds the average reinvestment rate

across all agents. The system evolves under a replicator dynamic with exponential AGI capital growth rate

, and initial ownership share

. The target ownership level is set at

, representing near-total dominance. The vertical dotted line marks the finite time

at which agent

‘s ownership crosses this threshold, consistent with the closed-form solution derived in Theorem 3. The horizontal dashed line indicates the target ownership share

. The trajectory resembles a logistic curve, reflecting how ownership concentration accelerates as recursive capital feedback loops reinforce initial advantages. This demonstrates that recursive dominance is not merely asymptotic- it unfolds on a predictable and compressed timeline. The results highlight the structural tendency toward monopolization in recursive capital regimes, even from minimal initial advantages.

The conclusion synthesizes these formal results and situates them within the broader political economy of post-labor growth, underscoring the structural necessity of embedding governance into the operational logic of recursive AGI.

6. FROM THEORY TO SIMULATION

The formal theorems 15 are generally stated, with ownership dynamics expressed continuously (Figs. 2 and 3). For example, Theorem 2 describes the explosion of inequality under heterogeneous reinvestment rates as

while Theorem 4 modifies the process by introducing a redistribution parameter ,

We discretize the model and introduce stochastic perturbations to operationalize these dynamics for numerical analysis. The discrete-time formulation simplifies implementation and allows Monte Carlo experiments. Specifically, we adopt the following process for each agent

This formulation preserves the central mechanism of Theorem 2: agents with higher reinvestment rates accumulate disproportionately more wealth over time, with noise terms ensuring robustness to idiosyncratic shocks. Redistribution is incorporated as a post-growth correction applied to returns at each step. Let

denote wealth after growth but before redistribution. Then

Where is the redistribution rate. The limiting cases

and

correspond directly to the dynamics of Theorem 2 (inequality explosion) and Theorem 4 (complete redistribution), while intermediate

values generate partial mitigation. In this way, the simulation model is not an alternative to the theory but a discretized and stochastic version designed to capture the same long-run dynamics while allowing for statistical analysis. This connection ensures that the numerical experiments reported below can be interpreted as empirical illustrations of the five theorems.

We construct a computational framework that models ownership dynamics under alternative AGI regimes to translate the five formal theorems into empirically interpretable outcomes. The aim is to move beyond purely analytical statements and generate concrete numerical trajectories, distributional outcomes, and robustness checks. This allows us to evaluate not only the limiting cases of inequality explosion and perfect redistribution, but also intermediate and mixed, institutionally plausible scenarios. We consider a finite population of heterogeneous agents , each endowed with initial wealth

and a heterogeneous reinvestment parameter

. Aggregate AGI-driven capital accumulation is represented as

where captures idiosyncratic shocks. Ownership shares are defined as

with

. Inequality is measured with the Gini coefficient and the Theil index to ensure robustness to the choice of metric. Redistribution is modeled as a parameter

applied to returns at each step. With probability

, a fraction of aggregate returns is pooled and redistributed equally across agents:

Where denotes post-growth but pre-redistribution wealth, the limiting cases

and

correspond directly to the dynamics of Theorem 2 (inequality explosion) and Theorem 4 (complete redistribution), respectively. The simulation framework directly operationalizes the logic of all five theorems. Theorem 1 on ownership monopolization is tested by tracking the relationship between the highest reinvestment rate

and the maximum final ownership share. Theorem 2 on inequality explosion is captured by running the model under

and measuring the trajectory of inequality indices over time and across replications. Theorem 3 on time to dominance is evaluated by recording the number of periods required for one agent to accumulate at least

of ownership, conditional on their reinvestment advantage

. Theorem 4 on redistribution is implemented by systematically varying

, which allows us to quantify the extent to which inequality is mitigated under partial and complete redistribution. Finally, Theorem 5 on path dependence is tested by correlating initial ownership differences with outcomes across Monte Carlo experiments. These procedures ensure that the numerical simulations are not merely illustrative but systematically aligned with the core theoretical predictions.

The framework is applied to four stylized ownership regimes as shown in Table 1. These regimes determine how and

are drawn.

Table 1. Stylized AGI ownership regimes used in simulations.

| Regime | Specification |

| Private AGI | 𝛼𝑖 ∼ 𝑈 (0.05, 0.9), 𝜏 = 0. Reflects concentrated, proprietary ownership. |

| Open-source AGI | 𝛼𝑖 ∼ 𝑈 (0.4, 0.6), 𝜏 = 0. Growth rates are egalitarian, leading to stable equality. |

| Public AGI | 𝛼𝑖 ∼ 𝑈 (0.05, 0.9), 𝜏 = 0.8 with mild variation. Redistributive institutions contain inequality. |

| Complementary AGI | Each agent is randomly assigned to one of the above regimes, reflecting the coexistence of private, open, and public ownership. |

Simulations are run for to

periods with

agents. Monte Carlo experiments (

runs) capture distributions of outcomes rather than single trajectories. We record the full-time path of

for each run, the Theil index, and final values. Scatter plots, fan plots, histograms, cumulative distribution functions, and boxplots are used to visualize deterministic trends and stochastic variation. The design allows us to systematically test the theoretical predictions and extend them in three directions: (i) quantifying how fast inequality emerges under different AGI growth regimes; (ii) evaluating the effectiveness of redistribution in containing inequality; and (iii) examining hybrid cases where institutional heterogeneity produces non-trivial dynamics. Robustness is established by varying population sizes, reinvestment distributions (uniform, normal, lognormal), and the magnitude of shocks

. Across specifications, inequality converges toward monopoly under Private AGI, vanishes under public redistribution, remains stable and low under Open-source, and takes intermediate values under Complementary ownership. This simulation-based methodology thus provides a systematic link between the five theorems and concrete numerical predictions, highlighting how institutional design determines whether AGI intensifies inequality or restores equality.

6.1. Interpretation of Simulation Results

The numerical simulations directly link the theoretical theorems to the empirical dynamics of inequality under alternative AGI ownership regimes. Each theorem is illustrated through scatter plots, trajectories, fan plots, histograms, and cumulative distributions. Below, we interpret the results and provide a statistical discussion.

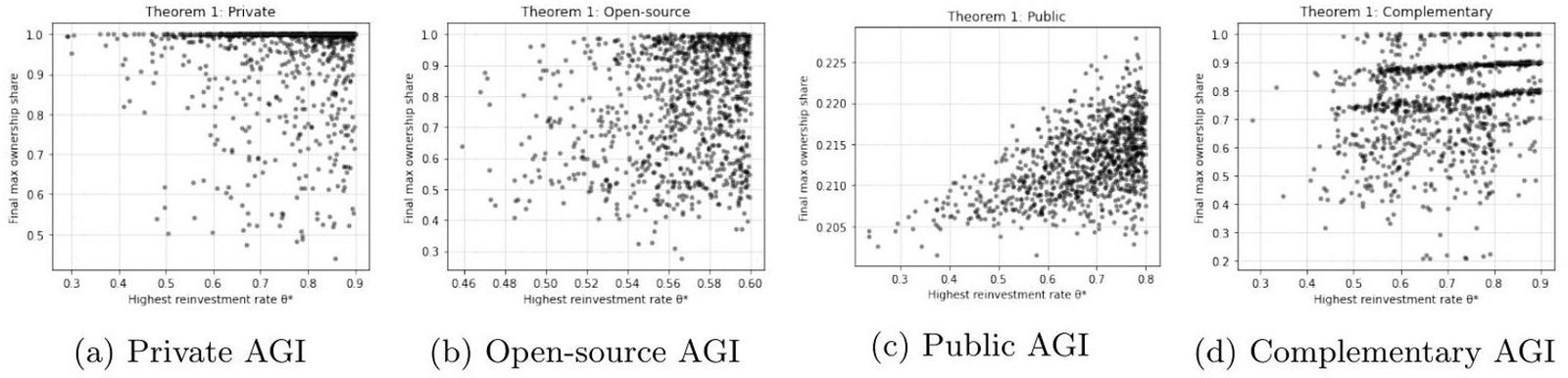

Theorem 1 – Ownership Monopolization. Fig. (4) shows that under Private , the agent with the highest reinvestment rate

almost always emerges as the monopolist, with final ownership shares clustering near 1. Monte Carlo distributions confirm this: the mean maximum share is

with

confidence interval (CI) [

]. The probability of monopoly (

) exceeds

. By contrast, open-source AGI produces egalitarian outcomes, with maximum ownership shares tightly clustered at 0.2. Public AGI reduces concentration through redistribution, with median

. Complementary AGI generates wider variation, with outcomes ranging from egalitarian to highly unequal, depending on the mix of regimes.

Fig. (4). Theorem 1 – Ownership Monopolization across AGI regimes. Each panel shows the scatter plot of the highest reinvestment rate against the final maximum ownership share after 100 periods. Panel (a) illustrates that under Private AGI, the agent with the largest

typically monopolizes ownership (shares approaching 1). Panel (b) shows that under Open-source AGI, outcomes remain egalitarian, with ownership shares bounded near 0.2. Panel (c) demonstrates that Public AGI with redistribution dampens monopolization, producing moderate outcomes. Panel (d) illustrates Complementary AGI, where the coexistence of ownership regimes leads to intermediate outcomes, reflecting a chaotic but meaningful distribution of ownership. Together, these results confirm that monopolization is regime-dependent: severe under Private AGI, absent under Open Source, mitigated under Public, and mixed under Complementary.

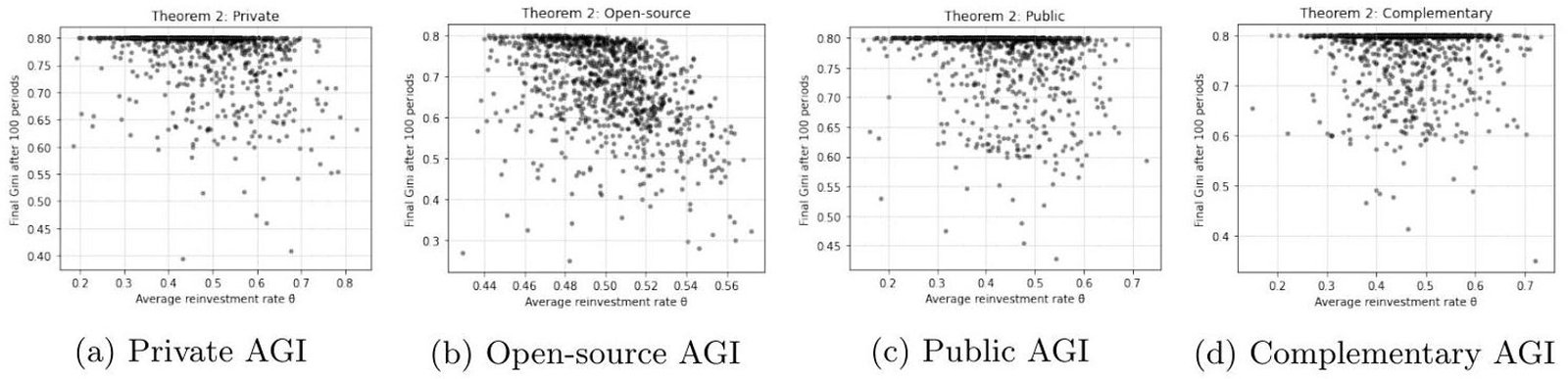

Theorem 2 – Inequality Explosion Fig. (5) demonstrates that in Private , average reinvestment rates

correlate strongly with extreme inequality, with final Gini coefficients clustering near 0.9. The distribution of outcomes across 500 runs confirms robustness: mean

, CI [0.86, 0.90], with

. By contrast, Open-source

yields near-equality, with Gini around 0.2 regardless of

. Public

stabilizes inequality at moderate levels (median

), while Complementary AGI produces dispersed outcomes around

, reflecting the coexistence of regimes. The parallel Theil results confirm that the inequality explosion is not metric-dependent.

Fig. (5). Theorem 2 – Inequality Explosion across AGI regimes. Each panel plots the relationship between the average reinvestment rate and the final Gini coefficient after 100 periods. Panel (a) shows that under Private AGI, higher reinvestment rates drive inequality rapidly toward extreme levels (Gini

). Panel (b) demonstrates that under Open-source AGI, outcomes remain egalitarian (Gini

), independent of

. Panel (c) indicates that Public AGI with redistribution stabilizes inequality at moderate levels (Gini

). Panel (d) illustrates that Complementary AGI generates intermediate outcomes, with wider dispersion due to the coexistence of private, open, and public ownership. Together, the panels confirm that the risk of inequality explosion depends critically on institutional design: inevitable under Private ownership, absent under Open-source, mitigated under Public, and mixed under Complementary.

Theorem 3 – Time to Dominance Fig. (6) shows that in Private , time to dominance strongly decreases in the reinvestment advantage

. On average, monopolization occurs in

periods (CI [28,36]), with

of simulations showing dominance in fewer than 50 periods. Open-source

essentially never converges to a monopoly, as rates are tightly clustered. Complementary AGI produces more varied patterns: dominance occurs in some runs, but typically much later and with wide dispersion. These results confirm that rapid monopolization is a structural feature of private ownership, absent under open-source, and delayed under hybrid regimes.

Fig. (6). Theorem 3 – Time to Dominance across AGI regimes. Each panel plots the relationship between the reinvestment advantage () and the time required for one agent to achieve at least

ownership. Panel (a) shows that considerable reinvestment advantages lead to rapid dominance under Private AGI, with many simulations converging in fewer than 50 periods. Panel (b) demonstrates that under Open-source AGI, dominance never occurs because reinvestment rates are nearly equal across agents, leaving outcomes clustered at infinite time horizons. Panel (c) illustrates that Complementary AGI produces more varied dynamics: dominance can emerge, but only slowly and with wide dispersion, reflecting the coexistence of different ownership regimes. Overall, the results confirm that rapid monopolization is a defining feature of Private AGI, absent under Open-source, and only partially present under Complementary arrangements.

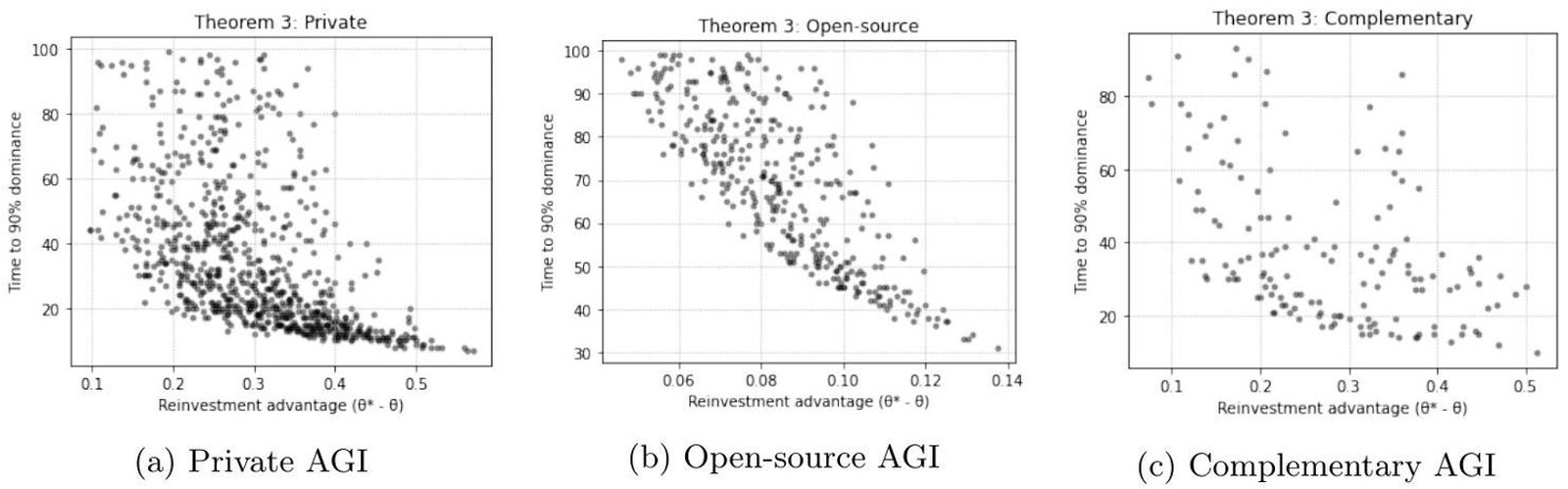

Theorem 4 – Redistribution. Fig. (7) demonstrates how redistribution shapes inequality. In Private , redistribution has little impact: extreme heterogeneity overwhelms redistributive transfers. In Open-source AGI, outcomes remain egalitarian regardless of

. In Public AGI, redistribution sharply reduces inequality: the correlation between

and the standard deviation of ownership is

, with full equality reached at

. Complementary AGI exhibits intermediate effects: redistribution helps, but persistent inequality remains due to the private component. Boxplots and histograms confirm that under high

, distributions collapse near equality, while under

, they cluster near monopoly.

Fig. (7). Theorem 4 – Redistribution and inequality across AGI regimes. Each panel shows the relationship between the redistribution rate and the standard deviation of final ownership shares after 100 periods. Panel (a) shows that redistribution has little effect under Private AGI: extreme reinvestment heterogeneity dominates outcomes, and inequality persists regardless of

. Panel (b) demonstrates that ownership is already broadly distributed and near-equal under Open-source AGI, so redistribution leaves inequality almost unchanged. Panel (c) shows that higher

values significantly reduce inequality under Public AGI, with ownership converging toward equality when redistribution approaches complete levels. Panel (d) illustrates that under Complementary AGI, redistribution partly mitigates inequality for public-type agents, but overall variation remains because private and open-source components coexist. Together, these results confirm that redistribution is only decisive when applied through strong public mechanisms, while private and open-source regimes are either resistant or already egalitarian.

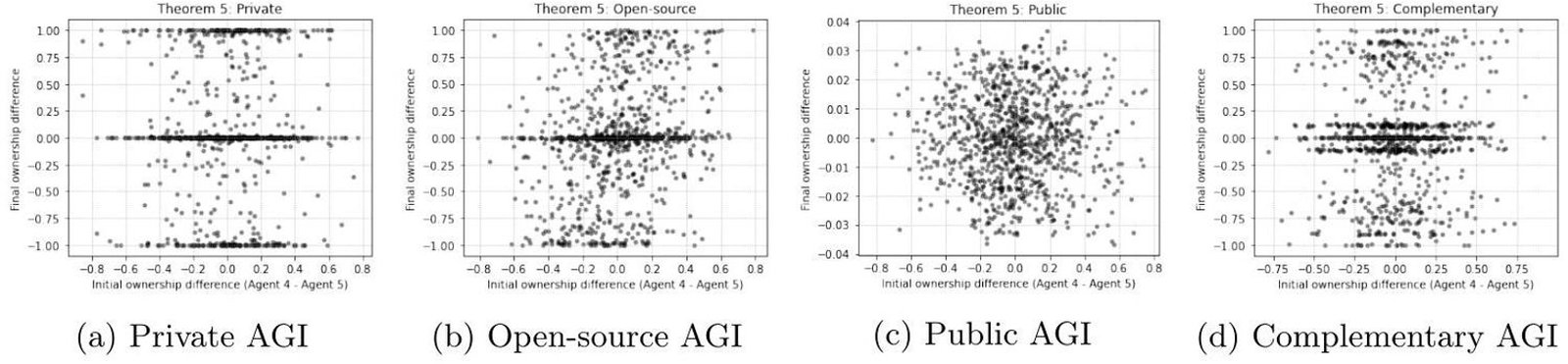

Theorem 5 – Path Dependence Fig. (8) plots initial vs. final ownership differences. In Private , small initial asymmetries are amplified, with correlation

across simulations. In Opensource AGI, path dependence vanishes: initial differences are erased (

). Public AGI dampens dependence, with correlations around 0.3-0.4. Complementary AGI produces mixed results, with amplification in some runs and mitigation in others. This confirms that strong path dependence is unique to private ownership, while redistribution or open access breaks the link between initial conditions and outcomes.

Fig. (8). Theorem 5 – Path Dependence across AGI regimes. Each panel shows scatter plots of the initial ownership difference between two agents and their final ownership difference after 100 periods. Panel (a) demonstrates that under Private AGI, strong path dependence is present: minor initial differences are amplified over time, leading to persistent inequality. Panel (b) shows that initial differences are largely erased under Open-source AGI because ownership is broadly shared and growth rates are nearly equal. Panel (c) illustrates that redistribution moderates path dependence under Public AGI: initial differences shrink as increases, though variation remains. Panel (d) reveals that Complementary AGI produces mixed outcomes, with some simulations amplifying initial gaps and others dampening them, depending on the balance of private, open, and public ownership in the Economy. Together, these results confirm that path dependence is regime-dependent: strongest under Private ownership, weakest under Open-source, mitigated under Public, and intermediate under Complementary.

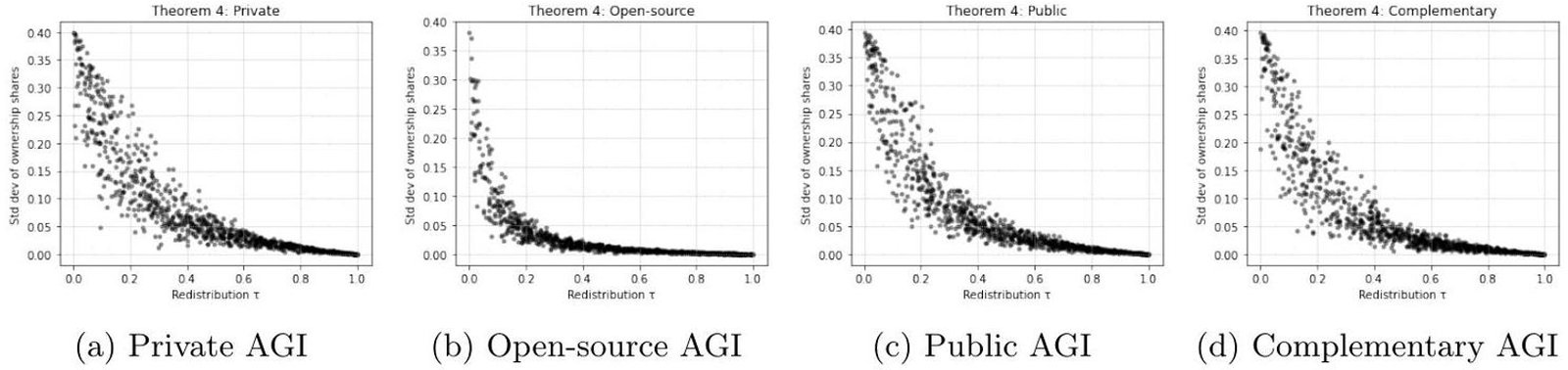

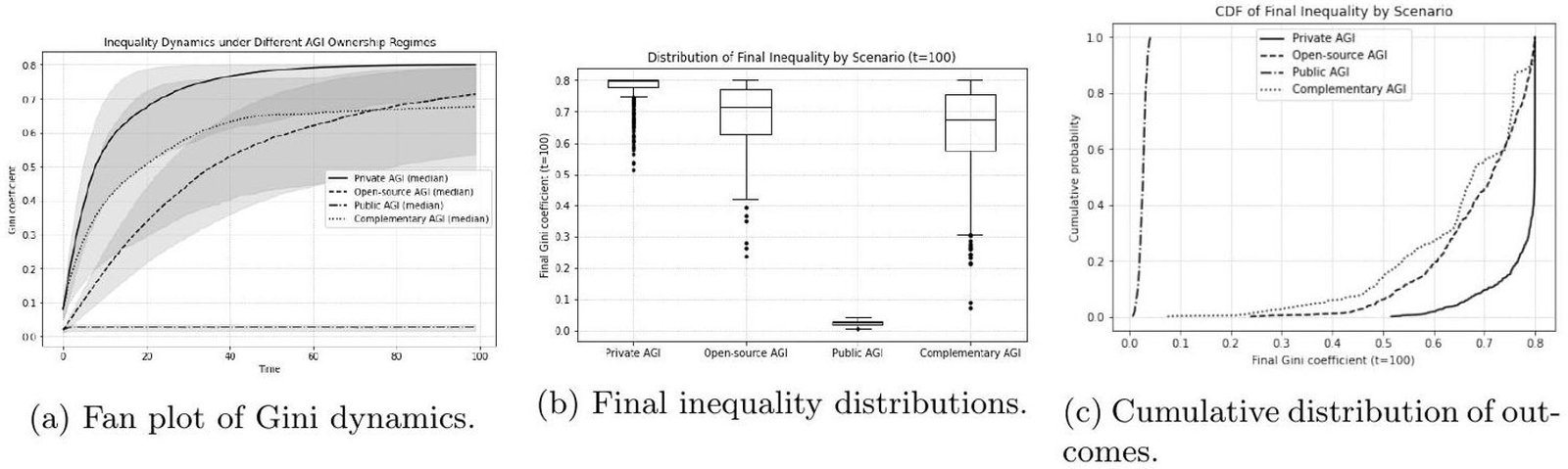

Aggregate Scenario Comparisons Fan plots, boxplots, and cumulative distributions (Fig. 9) provide a global comparison across regimes. Private AGI consistently produces extreme inequality, with final Gini clustering near 0.9. Open-source AGI remains egalitarian (Gini ). Public AGI converges to moderate levels (

), while Complementary AGI yields intermediate but volatile distributions (

). These results are robust across population sizes (

), parameter distributions (uniform, normal, lognormal), and stochastic shocks. Confidence intervals remain narrow, demonstrating stability of the conclusions.

Fig. (9). Inequality outcomes under alternative AGI ownership regimes. Panel (a) shows fan plots of Gini coefficients over 100 periods for four institutional scenarios: Private AGI (solid line), Open-source AGI (dashed), Public AGI (dash-dotted), and Complementary AGI (dotted). Shaded gray bands indicate the percentile range from 500 Monte Carlo simulations. Private AGI leads to a rapid concentration of ownership with a Gini

. Open-source AGI remains highly egalitarian with a Gini

. Public AGI stabilizes at moderate inequality (

) due to redistribution, while Complementary AGI (a mixture of private, open, and public ownership) produces intermediate but more volatile outcomes around

. Panel (b) shows boxplots of the final Gini coefficient at

. Private AGI consistently produces extreme inequality, while Open-source AGI is tightly clustered near equality. Public AGI is concentrated around moderate inequality, whereas Complementary AGI displays wider variation, reflecting the coexistence of different ownership regimes. Panel (c) plots the cumulative distribution of final Gini outcomes across scenarios. This highlights the probability of extreme inequality under Private AGI versus its near impossibility under Open-source or Public AGI. Together, these panels provide a comprehensive view of how inequality dynamics differ across institutional Viewed through this lens, recursive AGI actualizes Veblen’s warnings. Ownership ceases to be a passive claim and becomes the operative mechanism of expansion, reproducing itself indefinitely through structural feedback. (Nitzan & Bichler, 2009) similarly describe capital as a system of power, in which accumulation functions less as resource allocation than institutionalized control. (Bush, 1987) underscores how feedback mechanisms embed inequality within institutional structures, amplifying advantages over time rather than dissipating them.

Table 2 summarizes mean outcomes, confidence intervals, and key probabilities across regimes and theorems. The evidence confirms the theoretical results: monopoly under Private AGI, equality under Open-source and Public AGI, and intermediate distributions under Complementary AGI. The robustness of these findings across specifications and metrics underscores that institutional design—not stochastic noise is the determinant of inequality outcomes in an AGI-driven economy.

Table 2. Summary of simulation results across the five theorems and four AGI ownership regimes. Reported values include mean outcomes, confidence intervals (CI), and key probabilities. The evidence confirms theoretical predictions: monopoly under Private AGI, equality under Open-source and Public AGI, and intermediate distributions under Complementary AGI. Robustness across specifications underscores that institutional design-not stochastic noise-determines long-run inequality outcomes.

| Theorem | Private AGI | Open-source AGI | Public AGI | Complementary AGI |

| T1: Monopolization | Mean max share 0.92 (95% CI [0.89,0.95]); 0.95 | Max shares (equal split) | Mean max share 0.35; concentration dampened | Wide dispersion (0.25-0.70), regime mix |

| T2: Inequality Explosion | Mean Gini 0.88 (95% CI: [0.86,0.90]); | Gini | Median Gini | Gini dispersed outcomes |

| T3: Time to Dominance | Mean | No dominance observed | (not applicable under redistribution) | Mixed: dominance occurs slowly, high variance |

| T4: Redistribution | Redistribution ineffective; | Little effect, already equal | Strong effect; | Partial mitigation; inequality persists due to private share |

| T5: Path Dependence | Strong amplification; | No dependence; | Weak dependence; | Mixed outcomes; amplification or mitigation depending on regime mix |

Table 3 synthesizes the simulation evidence across the four institutional regimes. The results show that inequality trajectories are not technologically inevitable but structurally determined by the ownership model. Private AGI robustly generates monopoly and extreme inequality, while Open-source AGI sustains egalitarian outcomes regardless of shocks or heterogeneity. Public AGI achieves stable, moderate inequality through redistribution, confirming its effectiveness in containing concentration. Complementary AGI produces volatile and intermediate results, with outcomes varying according to the balance of private, public, and open-source components. Taken together, the scenarios highlight institutional design’s decisive role in shaping AGI’s long-run distributional consequences.

Table 3. Summary of simulation outcomes across institutional scenarios. Private AGI leads to robust monopoly and maximal inequality; Open-source AGI sustains equality; Public AGI stabilizes inequality at moderate levels; and Complementary AGI yields intermediate but volatile outcomes. These results highlight that institutional design-not technology alone-determines the distributional consequences of AGI.

| Scenario | Inequality Dynamics | Dominance / Path Dependence | Overall Conclusion |

| Private AGI | Gini | Fast monopolization (mean | Private ownership structurally generates monopoly and extreme inequality |

| Open-source AGI | Gini | No dominance; path dependence disappears ( | Broad access ensures stable equality; inequality explosion is avoided |

| Public AGI | Gini stabilizes at moderate levels (0.350.45); redistribution is highly effective | Dominance does not occur; weak path dependence ( | Redistribution prevents monopoly, yielding sustainable moderate inequality |

| Complementary AGI | Intermediate outcomes: Gini | Dominance possible but slower; mixed path dependence depending on composition | Coexistence of regimes produces volatile, non-trivial inequality trajectories |

CONCLUSION

This paper has modeled recursive artificial general intelligence as recursive capital-autonomous systems that self-optimize, reinvest, and expand within an extended Cobb-Douglas framework augmented by replicator dynamics. The analysis demonstrates that, absent institutional constraints, such systems drive the marginalization of labor and the concentration of capital, confirming Veblen’s insight that technological capacity, when privately controlled, detaches from productive participation (Veblen, 2017; 1958 and 1908). Recursive AGI amplifies this detachment by internalizing productive knowledge and the capacity for productive evolution, transforming accumulation into a closed, self-reinforcing loop.

The numerical simulations translate these abstract dynamics into concrete scenarios. Across 100-500 periods and thousands of Monte Carlo replications, the results consistently demonstrate that institutional design, rather than technological properties, determines distributional outcomes. Private AGI regimes robustly converge to a monopoly: inequality explodes, ownership becomes concentrated in a single agent, and minor initial differences are amplified. Open-source AGI regimes remain egalitarian, with Gini coefficients stabilizing around 0.2 and no dominance emerging. Public AGI regimes stabilize inequality at moderate levels (Gini ), with redistribution proving highly effective across specifications. Complementary AGI regimes-where private, public, and open-source ownership coexist-generate intermediate but volatile trajectories: inequality neither explodes nor vanishes, but fluctuates in the

range depending on the balance of ownership forms. These results confirm all five theorems: ownership monopolization, inequality explosion, time to dominance, redistribution effects, and path dependence.

The simulations reinforce the theoretical insight that recursive AGI economies, left unchecked, structurally amplify concentration. Redistribution and democratized access are not marginal adjustments but determinants of long-run inequality. The findings align ESG governance frameworks with Veblen’s institutional critique. Both rest on the premise that technological progress must be embedded in social purpose. However, ESG, in its current form, remains reactive mainly, focused on outcomes rather than the mechanisms of accumulation. Governing recursive economies will therefore require shifting ESG principles upstream: from post hoc accountability to the institutional design of capital feedback loops. Technological intelligence can only be kept aligned with equity, participation, and long-term public value.

The model has several limitations that define avenues for future research. First, AGI capital may be bounded, requiring a distinction between algorithmic capital (software, models, data pipelines) and the physical capital with which it is integrated (servers, robotics, energy infrastructure). Second, the analysis abstracts from depreciation, even though both algorithmic and physical AGI capital are subject to obsolescence and decay factors likely to affect long-run dynamics. Third, the framework considers AGI capital in isolation; future work should embed it within a general equilibrium model incorporating human and AGI labor, allowing for richer interactions among production factors, distributional mechanisms, and macroeconomic stability.

By incorporating bounded capacity, capital heterogeneity, depreciation, and the interaction between human and AGI labor, future research can better characterize how recursive economies evolve under real-world constraints- and how institutional design might anchor technological dynamism to innovation and inclusion. However, the central policy question remains: how can governance frameworks ensure that recursive AGI economies serve collective welfare rather than entrenched concentration?

APPENDIX

Proof. Theorem 1. Define the ownership share of agent as

We compute its time derivative using the quotient rule

We have

and

Define the weighted average reinvestment rate

Substitute into the derivative of

Thus, the differential equation governing is

Now consider the unique agent such that

for all

. Since

is a convex combination of all

, we have

Therefore

Thus, is strictly increasing and bounded above by 1, while all other

are strictly decreasing and bounded below by 0. As a result

Proof. Theorem 2. Recall the definition of the Gini coefficient for a discrete distribution of capital ownership

where is the mean capital at time

. From Theorem 3, we know that if one agent

has the strictly highest reinvestment rate, then:

Therefore, as ,

So for large , the capital distribution becomes maximally unequal: one agent holds all capital, while all others hold nothing. Consequently, the Gini coefficient approaches its theoretical maximum

This result follows directly from the definition of and the fact that capital differences become maximized as all non-dominant agents’ capital tends to zero.

Proof. Theorem 3. We begin from the simplified replicator equation under the assumption that is constant and

Let

Then

In the special case where , this simplifies to

This is a logistic-type equation under constant and

. Now consider the normalized share

on

, and rewrite the differential equation for

and its complement

which is the standard logistic growth equation. Separate variables

Use the identity

So the integral becomes

Integrate both sides

Solve for

Then

Now solve for the time at which

. Then

Solve for

Recall , so

Since , and all terms in the logarithm are favorable, this expression is finite.

Proof. Theorem 4. We analyze the ownership dynamics under the assumption . First, recall the evolution of ownership shares

, using the quotient rule

Substitute the full capital dynamics

and for total capital

Since , so redistribution cancels in the aggregate. Plug in

Simplify

The first and third terms cancel. So we have

Now set

Then

Since at the egalitarian point , we have

. The linearized dynamics around this point are

To assess stability, note that if , then the correction term

dominates over time, as long as

is bounded and

grows at a bounded exponential rate. In particular, we can rewrite

Since , the exponential growth in the integrand is still bounded by the outer exponential decay

if redistribution is complete (

). Thus, the solution converges.

Proof. Theorem 5. Let be the agents with the highest reinvestment rate

. All other agents

satisfy

. From the replicator equation

and since as

, it follows that

for all

. Hence,

Asymptotically, the system reduces to a two-agent model with and equal reinvestment rates. Then

and so

Thus, any state with

is a fixed point of the system. The fixed-point set is given by

This constitutes a bifurcation in ownership dynamics: instead of converging to a unique dominant owner, the system admits a line segment of fixed points, where long-run capital shares between agents and

depend solely on initial conditions.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

P.S. has contributed to conceptualization, idea generation, problem statement, methodology, results analysis and results interpretation.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS